This text is a slightly adapted keynote/film introductory note I gave at a conference when the Department of Media and Social Sciences at the University of Stavanger celebrated its 50th anniversary, April 28, 2022. After the speech, our film Jew Man Business was screened.

In many ways, ethnography is akin to journalism. The researcher or journalist visits a somewhat unfamiliar place and tries to understand what is happening. In my research, I have focused on understanding civil wars: why people fight, how they survive, and how they rebuild their lives in the fragile aftermath of conflict. Foreign correspondents, stringers, documentary photographers, and documentary filmmakers often go to the same places, speak with some of the same people, and ask similar questions. In this talk, I will share some of my experiences from the ethnographic fieldwork I have conducted over the past 25 years. I will also present a shorter film we made to contrast with the many journalistic works and documentaries on civil wars in Liberia and Sierra Leone. Although I believe some journalists are careless and sometimes question their ethics, rather than a critique, this talk aims to find common ground between modern anthropology and journalism.

I have studied civil wars since I first got stuck in one in 1996. It was in Liberia. At the time, I was conducting three months of fieldwork in neighbouring Côte d’Ivoire, focusing on refugees from the ongoing civil war in Liberia. As I had subsequently intended to study refugees returning to Liberia, I seized the opportunity to travel overland to Monrovia, the Liberian capital, with an NGO vehicle. There had been no fighting for some time. However, on the way down, we encountered innumerable checkpoints manned by young, sometimes very young, rebel soldiers from various military factions. Approaching Saniquellie in Nimba County, we were stopped at a checkpoint by a group of young soldiers.

They were all smiles. I couldn’t resist stepping out of the white car and asking for a photo. They happily posed. At the time, I didn’t realise it, but the yellow T-shirt with the print “patience my ass” became significant for my research on child and youth fighters, as it turned out that many joined war factions in a more voluntarily fashion than media and other written accounts suggest. They were frustrated by the system, experiencing social blockages or a sense of social death. They were running low on patience. For many, fighting was a “patience my ass” move, a way of forcing themselves out of the margins and into the centre of society. In hindsight, it was a move that, for a clear majority of rank-and-file soldiers, did not succeed.

My primary focus during a one-year field study in 1997-98 in Monrovia and Ganta, Nimba County, was on what motivated young people to join rebel groups and the tactics they used to reintegrate into civil life.

However, the year before that, I became stranded in Monrovia and had to be airlifted out of the country. Two days after the encounter at the Saniquellie checkpoint, the war reignited. Had I known what I know now, I would have recognised the apparent signs of troop build-up and the movement of personnel, though travelling as civilians and unarmed, along the road we took. I would have understood the increased tension at the checkpoints. The following year, when I returned to Liberia, a young man, whom I knew from a refugee school on the Ivorian side of the border, told me he had seen me, and even attempted to catch a ride with our vehicle when he was moving along the road towards Monrovia to once again fight in the war. I did not see him, nor was I aware of the troop movements. I was a naive newcomer to war.

The day after I entered Monrovia, rebel forces clashed in what became the worst fighting in the capital during the entire civil war. It was gruesome, and from the balcony of a downtown flat I was stuck in, I could see mainly youths shooting at each other. I would say that most soldiers were between 16 and 21 years old.

After two days of intense fighting, a pause occurred, and I managed to make my way up the street to the US embassy. Inside, however, it was not much safer. Rebels jumped the poorly guarded walls and fought each other on the premises. When I went for a shower, I looked out the window and, to my surprise, a rebel soldier was hiding, pressed up against my window. When he saw me, he raised his finger to his mouth, “Shhh.” I closed the curtains and let the warm water rinse my body, as if the war was not there. A few nights later, we boarded a helicopter. I had a Liberian child on my lap, and he peed in his pants as we left Monrovia. Rebels were shooting at us, and a machine gun at the rear of our helicopter returned fire—bullets directed towards a pitch-black capital. We were mainly expats, but there were a few Liberians with American citizenship.

This highlights my privileged position. When conditions become difficult, people like me can usually find a way out. No one at the U.S. embassy was aware of my identity or the reason for my visit. Neither did they appear particularly interested, but they still allowed me in. The colour of my skin acted as my passport. Most Liberians, however, remained on the ground, fighting for their survival; tens of thousands lost their lives in the weeks that followed.

When I returned to Monrovia eight months later, elections had taken place. Charles Taylor, the warlord of the most significant rebel movement, had won convincingly and was installed as president. A reminder that democratic elections do not always guarantee democracy.

I began to spend time with former youth soldiers in downtown Monrovia. They were pretty excited to discover that I had been in Monrovia during the previous year’s war. If only in a cursory way, I had experienced their war, and it turned out to be a vital door-opener. I asked them about their whereabouts the previous year. As they were among the groups controlling the downtown area, they shared stories of how, whenever there was a lull in the fighting, they were approached by Western journalists. Some of them had been guides for these journalists. From the start, the journalists only dared to walk a few blocks. They stayed on a line, guarded by the rebel soldiers. They took photographs of the same few objects, the same ruins, and sometimes the same human remains. And they were fed the same few stories. Given the limited access, I have always wondered what it truly means to report unbiased and balanced news from a place like this. Is it even remotely possible?

Many of the soldiers who guided the journalists came to regret this. Indeed, they had been given tokens for their work, but journalists often promised them that upon their return, they would help them get on with their lives, pay for an education, or merely buy a mattress they could sleep on. The group I came to work with lived in a concrete shell of an old factory. During the rainy season, it got cold, and a foam mattress between them and the cold ground would make all the difference. However, few journalists ever returned, and not a single one kept their promises. Broken contracts between them and journalists made my work difficult. Why would they trust me? And from my point of view, what stories would they feed me with?

Rebel guides took the photojournalists on a safari-like walk through the urban wasteland when there was no fighting. To visualise war, the ex-combatants I worked with recalled that they were at times asked to perform active war. Many photographers and filmmakers were not on the front lines; instead, they stayed at a hotel near the U.S. Embassy, which was considered a safe haven. It was simply too dangerous out there. Instead, they worked post-fact by recreating scenes. Rebel soldiers assist them in staging the war for the cameras.

I cannot say how frequently such acts happened, but when I mentioned this fact a few years ago while giving a lecture to a group of UN peacekeepers, one participant in particular nodded in agreement. Later, he sent me a PowerPoint presentation that had circulated among his colleagues, which included 15 slides with “rigged” photos from fighting in Monrovia. Here are some:

Many poses or fighting styles mimic those seen in action films and are, quite frankly, not very effective in real war. In the background of the first picture, you can see other photographers taking photos. One is directed towards the same rebel soldier, whilst the other is taking a photo of a guy pointing his gun directly into the ground.

Another interesting point is that soldiers often appear very young—sometimes too young to handle a Kalashnikov, given its weight and strength. A boy around 13 or 14 might be able to hold a lighter Italian or Israeli machine gun, but not these types. This is what experts have told me. A more plausible explanation for the photos is that many of the younger individuals in the frames were Children Associated with Armed Forces (so-called CAFs), but not actual fighters. They performed various support roles for older soldiers. They cleaned and carried guns when there was no fighting. Therefore, during lulls in the battle, they posed with guns in front of international photojournalists, reinforcing stereotypes of child soldiers being exploited in African civil wars.

On the streets of Monrovia, I heard numerous stories of children trying to survive by telling violent tales to journalists. One was a young boy, whom I also saw in several news reports. As a reflection of the world’s absurdity, I saw him on a printed card from an international aid agency working against the war. It showed him on the ground; he looks stressed and agitated, as he displays his “warface.” In his hands, he holds a Kalashnikov. At the time, everyone in downtown Monrovia was familiar with the boy. He was poor and homeless, living day to day. Yet, everyone agreed that he never fought. Nonetheless, he mastered the art of telling his war story through words and body language.

Several of the guys whom journalists had approached told me that it was the journalist, or more probably the local fixer of the journalist, who arranged weapons for the photo shoots. They hired it from an ill-paid soldier or the like, thereby becoming an intricate part of a post-war economy.

So, if we go back to the pictures, we can’t simply conclude that they are genuine. The third picture in this batch is definitely not. It has been used to illustrate child soldiers in the media, predominantly on social media. Still, it is taken from a fiction film called Johnny Mad Dog, directed by Jean-Stéphane Sauvaire. He has made several fiction movies that are very close to being documentaries, and in this film, he trained local youth to become actors.

A few years ago, I collaborated with Clair MacDougall, a journalist who had lived in Monrovia for many years, on a project about some of the actors in this film and how they navigated Monrovia in the aftermath of the Johnny Mad Dog movie, rather than the war itself. One of the main characters, who never fought in the war, often portrayed himself as a former child soldier—another unusual legacy of a fictional film. In the end, we never managed to write up the research, but this case is another clear example of how young people invent rebel personas to cope in the post-war period.

Images travel! In another weird twist, an image from the film (on the right-hand side) became the cover of a book from Brazil.

I wrote to the author to ask him about the background of the image, and he had found it in a local gallery. While requesting permission to use it on his book cover, he never considered asking the artist where it originated. He took it for granted that it was from a favela in Rio de Janeiro.

I will return to Liberia soon, but first, I want to discuss the fieldwork I did next. After finishing my PhD, I moved there and started spending time on this street corner in downtown Freetown, the capital of neighbouring Sierra Leone.

One corner of the intersection was called Pentagon, another was named Israel (second picture), and the Pentagon residents carried out their more legal activities in Pentagon—mainly washing cars—while they engaged in illegal activities, such as selling and taking drugs, in Israel. A third corner was dubbed Baghdad. Overall, a rather striking reminder of world politics.

I spent two years hanging out on that street corner—any hour of the week, any time of the day. Ten to fifteen people, mostly former combatants, became my main interlocutors. Since then, we have stayed in touch. I have followed them through their post-war traumas, understood their war dilemmas, and seen how they have struggled to survive and reconnect with society. They once said they felt stuck and believed they would never progress, but now I meet a group of middle-aged men, many of whom have children and stable jobs. On the other hand, many of them are no longer with us. The post-war period proved to be almost as perilous and uncertain as the war itself.

I risk losing you here, but I want to discuss ethnography, anthropological work, and the danger of appearing anecdotal. I mentioned I worked with 10-15 people. That’s not many. Can you truly generalise from such a small group? Can it be compared to a survey of 2-3000 former combatants? Reflecting on the two years of street ethnography, I would say that my sample included far more than just 2-3000. Roaming the streets with Pentagon guys visiting all parts of the town, and taking my old, battered jeep to remote interior areas, where we visited their families and old combatant friends, I suggest that the material I have gathered carries more weight than just 2-3000 one-off interviews. It has both breadth and depth that surpass what most quantitative research can ever envisage. And now, it spans twenty years as well, as the cherry on top. On the contrary, I question some of the findings produced by quantitative researchers regarding the civil wars in both Liberia and Sierra Leone. Quite often, their findings do not add up.

When I began my ethnographic fieldwork with the Pentagon guys, I recorded life story interviews with them. After two years, I followed up, but most of their responses had changed. Once they got to know me and realised that I could be trusted and would not misuse their stories, they became more open and adjusted their narratives to something closer to “truth”. Besides the usual scientific rigour, ethnographic fieldwork relies on three main pillars: time, trust, and a good contextual understanding – the latter partly gained by reading historical and sociological books; however, these are scarce when it comes to small African countries. Gaining a profound knowledge of history and contemporary society requires being there. Understanding the sociology of war takes time; there are no shortcuts to this complex subject.

When researching sensitive areas such as participation in rebel armies, acts of killing, maiming, raping, pillaging, and destruction, it should be pretty clear that those you speak to may not readily admit to having committed such acts. Instead, they are more likely to share their victim stories. My “claim to academic fame” is the concept of victimcy. I define it as a tactic or agency of presenting oneself as a victim. When I began my research on child soldiers in Liberia, I met many young people who were surprisingly willing to discuss their wartime experiences with me. Some of them, like Benjamin Bonecrusher in Ganta, told me long stories about how brutal he was during the war, but as time went by, and I even became friends with his dad, he agreed that he had never fought. Benjamin and his peers were on a mission to gain an education, and they often pretended to be combatants, while in reality, they were not, to evoke sympathy and help them move forward in life. Others, of course, did fight.

When I first spoke to former combatants, their accounts of how they joined were very similar. They had either been forcibly taken by rebel soldiers at gunpoint or faced a choice: shoot a relative or an elder in their village, or join the ranks. More often than not, they were then loaded onto the back of a truck and taken away from their villages. They received brief training before being sent to the battlefield. It all seemed rather straightforward. Indeed, it fit so well with what I already knew—what we in the Global North believe to be true. Every single person I talked to had been forcefully recruited.

Over the next few months of my fieldwork, however, the stories began to shift, and in time. Stories changed gradually, and they rarely acknowledged that what they first told me was false. But there was no need to. It is easy to understand that you will not, in front of a total stranger, blurt out that “I killed and maimed and I volunteered to do so.”

In the end, not a single person I worked with maintained their stories of being forcefully recruited. Yet I still do not suggest that all people readily joined the carnage of war. Because they did not, but if they were forced into battle, it was instead due to structural forces. This is what I have been busy uncovering in my research. Part of the reason stems from a deep societal roar of dissatisfaction leading to a “patience my ass” move, and I am paraphrasing the yellow T-shirt, where you try to topple a dysfunctional system. Or you fight your way out of the margins. But many joined to protect what is theirs— their family’s, their kin’s, or their community’s.

I searched my photo archive for a series of pictures but couldn’t find them. The photos are again from the Pentagon street corner in Freetown, on a muddy stretch of road. A young man poses in a smart white suit. He looks pretty out of place. In the second photo, I photograph him from behind, and then it becomes clear that the back of the suit is entirely missing; it’s held together with a single string. Research is like that; it is often not as it first appears, and sometimes, what you don’t see at first is the most important.

To me, this highlights the value of ethnography. We often say that anthropologists understand what people do, not just what they say they do. First and foremost, people do not always want to disclose everything to a stranger or researcher immediately. Why would they? However, there is another aspect: research participants themselves often overlook aspects that we are interested in knowing. It often takes time to put words to experiences, and sometimes it takes a considerable amount of time. I believe you have all experienced this. When participating in a survey, there are questions you can’t fully relate to or even understand, but you still tend to tick a box. Do you prefer not to tick the “I don’t know” box? I tend to avoid that. I often wonder about these results, and I think this applies to much of a survey’s interview material.

A few years ago, a survey agency phoned me and asked if I could spare 20 minutes to answer some questions. It was one of those surveys about media behaviour, advertising, and consumption, etc., etc. I replied, “Yes, but is it okay if I lie?” The person on the other end of the line got very upset. I guess she would have been more than happy if I had just answered the questions and lied quietly here and there. Ignorance is bliss.

What you see is not always what you get. Remember the guy in the suit.

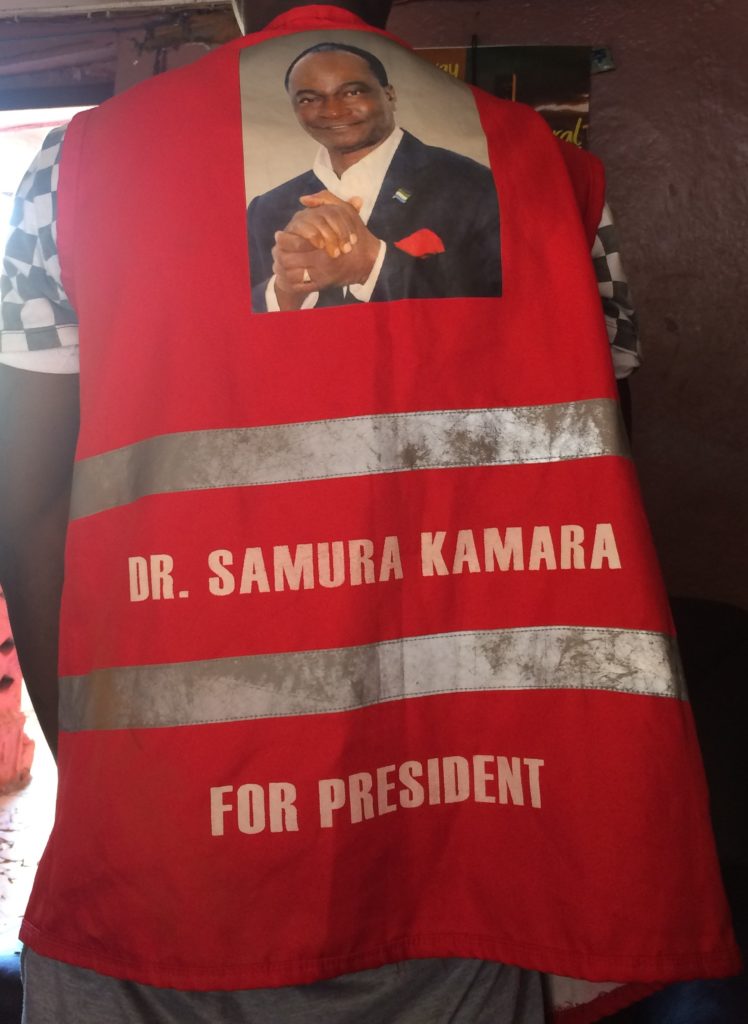

What does this image tell you?

I have worked extensively with photography over the years. I have also taught visual anthropology and sensorial ethnography, although I do not consider myself a visual anthropologist. The film Jew Man Business, which I will show in a few minutes, bears the subtitle “a documentary,” a designation we added to indicate that the film does not conform to the norms of visual anthropology. However, the film is intended to tell a different kind of war story – or perhaps more precisely, a post-war story. It is a response to the numerous documentaries made about the civil wars in Liberia and Sierra Leone, specifically, but also across the world.

Film language is inherently based on simplifications, narration, and images that can be related to; otherwise, it would not communicate effectively with the audience. Our “Northern-produced” documentaries on Liberia and Sierra Leone depict their wars, but with images adapted to fit our imagination. In many ways, such documentaries are extensions of colonial and missionary accounts. It is the strange and the violent—the oftentimes “uncivilized” and the ungodly. The plastic mask in this image—the last image—is most likely first sold in a European shop, carrying a set of meanings that transform in an African setting. It doesn’t matter that it is used in a carnival in Sierra Leone. We imagine the image elsewhere: as part of a brutal war, fought by people with logics and means radically different from ours.

The simplicity of the African ‘other’ also appears in ideas about dancing. Africans dance in rain or shine, or play, for that matter. One of the most experienced Swedish Africa correspondents noted in a report on the war in Liberia that “When there are no ongoing battles, they play war.” On the screen, there were images of young Liberians shooting at each other. These images, like those I showed earlier, were acted out, I argue, but they didn’t “play” because a sudden playfulness overcame them; they performed in front of a Northern media audience, hoping to gain some financial benefit from it.

The exotic often featured in documentary and journalistic media, as well as in many academic writings, blocks our understanding of what truly happens on the ground. In our film, we aimed to focus on the familiar rather than the exotic. We sought to portray our experiences of former combatants and street dwellers as deeply human, or perhaps even superhuman. Therefore, by employing tropes such as love and hope instead of aggression and despair, we introduce new perspectives to the audience, I hope.

Yet, having said that, it still largely depends on the audience. When I have shown the film to African audiences, there have been many laughs. However, when it has been screened for Northern emergency and development workers, there is instead a lot of “å det är så synd om dom” – feeling pity for them. Considering your backgrounds as journalists and media scholars, it will be interesting to see how you react.