No, you can’t! My wife has just politely asked if she can take a picture of a mural in a Korean restaurant we pass in Vietnam’s capital, Hanoi. Crowds of tourists are in the city, and it is little wonder that they are slightly tired of us. But it is a wall she wants to photograph!

I’ve spent most of my life travelling the world, both as a tourist and for work. Over the years, I have seen how travelling itself and the view of travellers have changed and thought a lot about how we as travellers should relate to it.

The first time I visited Vietnam was in 1995, soon after the country re-opened for tourists. There, as in many other places, children came running and demanded to be photographed. If you asked adults, they were happy and often proud to pose. Sometimes, they almost demanded that you take a picture. With the analogue cameras of the time, with limited amounts of film, you had to devise strategies to avoid taking too many pictures. Today, it’s not like that; even the kids don’t say, “Hey, take my picture”, anymore. Instead, you’ll often see some pretty annoyed expressions or people turning their heads away when a camera or phone is brought out. Taking photos of people we don’t know is no longer acceptable. How did this happen, and is it a bad thing?

Vietnam 1995 – photography by the author

The first reason is that we now have an enormous amount of tourists travelling to all corners of the world. Tourism is flooding the world, and we’re crashing into people’s backyards in a never-ending stream. Vietnam is just one of the hundreds of countries that get an overdose of tourism every year. I am currently in the small coastal town of Hoi An. It has a fantastic old city centre. Hundreds of thousands of us know it and take advantage of it. Everywhere you turn, there is a tourist. All the houses have been converted into restaurants, cafés, shops and massage parlours catering exclusively to tourists. Every house is stylishly refurbished, catering to our abstract nostalgia of French Indochina. Yet it gives an aftertaste of being in a theme park at Disneyworld. Who wants to live here? Who can live here? Outside the city centre, it is quieter. Still, if you follow the smallest little alley, you soon stumble over a “Homestay” or a “Villa” that is deliberately nestled in this particular neighbourhood, or rice paddy, for the tourist to experience the “genuine” or “original”. We meet tourists in droves on wobbly bicycles behind a guide who shows them the “real” Vietnam.

My family and I lived for a few years in a beautiful old train station back home in Sweden. It was not uncommon for tourists to stop outside and photograph our house. Once, when the whole family was having a weekend brunch in our pyjamas, a tourist picked up the camera and took a picture of the house and us through the window. My wife gave the finger and fervently hoped they would later zoom in on the picture and see it. No one likes a tourist. In Old Uppsala, they are an occasional one, but in Hoi An, we come in swarms.

In another over-touristed city: Kyoto, Japan, you see signs in some residential areas prohibiting photography. There are also crowds of tourists there. Most are respectful with their cameras, but not all. A video clip is circulating of a tourist repeatedly running in front of a geisha (or is she a maiko?) to take her picture. The geisha makes it overwhelmingly clear that she does not want to be photographed. Still, the parasitic human continues, unable to understand that it is not within her privilege to do so. For this, of course, she has also been pilloried on all sorts of online forums. While singling out individuals and subjecting them to online hate is probably not the right way to go, as tourists and visitors, we should think a bit more about how we take photos when we travel. When do we bother people who did not ask to be tourist objects?

A likely second reason for a reduced acceptance of our photography is today’s awareness of how widely images are circulated. Most countries, including Vietnam, use social media and have come to understand how quickly images spread. With the mobile phone camera, most people have first-hand experience of how it works, but they also have first-hand access to ‘our gaze’ – how visitors see them. They see our photos and often read our comments. This is not always appreciated. At its core, this scepticism about how we portray others is nothing new. During my years in the West African countries of Sierra Leone and Liberia, I was often told that Westerners were only photographing them to make money and that we looked at them like animals in a zoo. We want to see them half-naked in the wild or photograph them intoxicated and crazy with weapons. Or why not in some strange ritual?

“People not yet overtaken by civilization” is a tourist phenomenon. My wife and I recently spent a month in Laos, a country that is also becoming increasingly touristy. In the city of Louang Prabang, we booked a day of canoeing in the beautiful river landscape but were initially herded into a minibus with other tourists. The first stop was a tourist village containing mountain people dressed in traditional costumes and selling all kinds of stuff. They all wanted us to take pictures of them. An economic strategy, of course, but it felt both painful and tragic. They showed us their “authentic” culture 20 meters from the road in a dusty alley. In addition to their culture, they also played on the delicate strings of our culture by being represented mainly by women – one woman demonstrated how they hunted wild boar, even though in their culture, as in ours, it is mainly men who do it. The vendors were old or pregnant women, and the children they brought with them were dirty and snotty, all to fit our cultural stereotypes of their poverty.

A few weeks later, when we were up in the mountains in the north of the country, we lived among other mountain people. Here, tourists were few and far between, yet there was a clear awareness of our photography. Portraits were avoided, and we should not take pictures in people’s homes. One elderly man started grumbling when we photographed a suckling sow; no children suggested we photograph them, and everyone kept the photographer an arm’s length away. We got more direct contact only in the house where we slept and where we could communicate with the owner over a meal and some local brandy. Then, the opportunity to photograph the family also opened up.

This awareness and ability to say no, or at least express dissatisfaction, is fundamentally sound. This is the third reason why the possibilities of photographing people have changed. An awareness of post-colonial world order and global injustices is not new, but with the internet, social media and rivers of tourism, these injustices have become overt and inescapable. While the average person in Vietnam is economically much better off than when I was here 30 years ago, their knowledge of who the tourists are has also become much more evident. Vietnam produces a vast amount of our clothes, sneakers, etc., but the country, and more especially the common man, gets a very small share of that profit. Turning your face away or saying no can be seen as slightly resisting the global world order. It is primarily a sign of good health. A small one, but still.

For a long time, I used the camera to communicate. I picked up the camera and asked if I could take a picture, and after the picture, we started talking. The camera opened up. I experienced things through the camera. Back in 1989, in Indonesia, I met a man smoking outside his house on a garbage dump. It was at dusk, and I told him it would make a beautiful picture. Without hesitation, he agreed to have me photograph him as a proud homeowner. After that, he invited me to dinner. It was simple food in a very simple house – which it probably always is if you can only afford to build a makeshift home on a dumpsite. He had worked at Siemens in Germany, so we talked all evening, both of us in broken German. When I left, I was so full of life!

It started when my system camera got in the way while I was living in the conflict areas of Liberia and Sierra Leone. To people, it signalled that I was a photojournalist – which I was not. I noticed how they recoiled when I had the camera with me, which they didn’t normally do. I got a smaller camera to use when travelling. It worked for a while, but now I find even the cell phone gets in the way. It, too, creates a distance between me and the place I’m visiting. And the people. Of course, reducing the camera size was the wrong way from the start: trying to make my habit of photographing invisible. The camera was supposed to be a communication tool. That’s where I went wrong. I wanted to photograph to show the world in all its richness, not to engage in spy-like behaviour. We must photograph with respect, and we are probably doing something wrong if we need to hide our cameras.

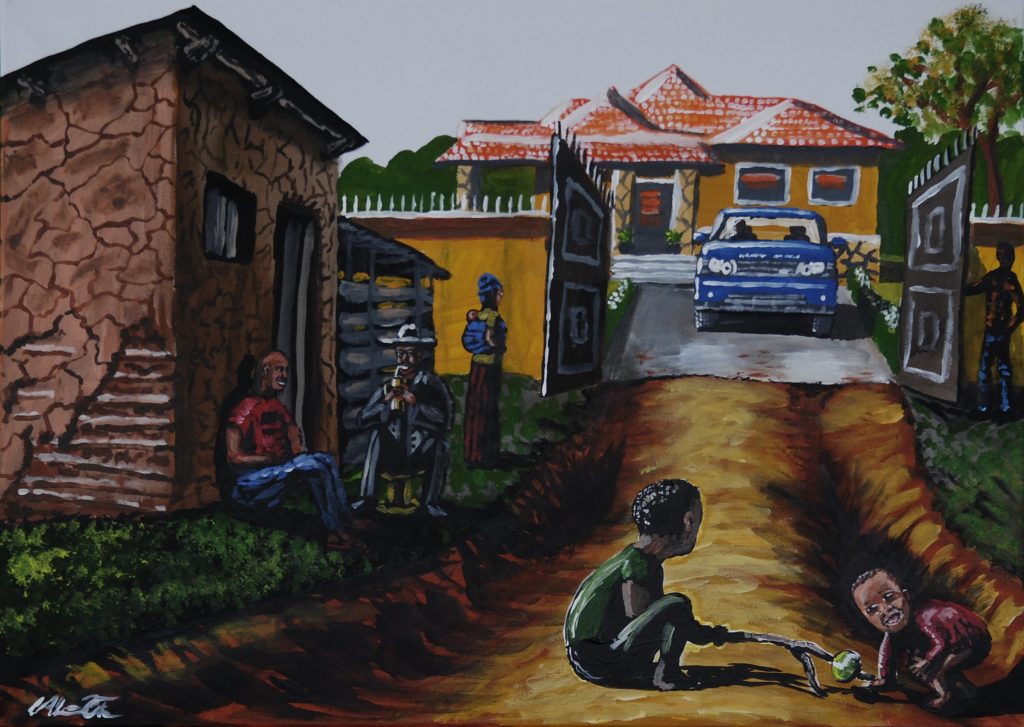

Hoi An, 2025, slightly outside the tourist zone – photography by the author

Travel photography has profoundly changed over my years of travelling the world. Yet it is far from dead. Nature is there, and the fellow travellers and poetic compositions of the city and countryside are still numerous. The opportunities to photograph “locals” are still there, but now have to be done more on their terms. A little more is required of us today—a greater investment in the encounter. We need to be genuinely interested in the people we meet. We can’t just walk by and throw up the camera – which we should never have done in the first place. We need to spend time with the people we want to capture. Then and there, we may suddenly find ourselves taking photos again. We might even be asked to do so. However, to do so, we need to travel slower. Stop for longer. When we stop for real, we can still photograph people in all their beauty.

There are still so many lovely, exciting faces, spectacular events, and environments that I would like to photograph, but I refrain from them today. I have to accept that I am the guest and that I am not the one in charge. Instead of pictures on my hard drives, I am re-training my head to collect mental memories better. I get to walk around and look, try to understand, ask questions, and soak up the realities that contrast my everyday life at home. After all, that’s what makes me travel.

Mats Utas is a researcher in cultural anthropology. He has lived in West Africa for several years and has travelled around the world for almost 40 years. He is not a photographer but has made both photo exhibitions and documentary films. He currently lives in Hoi An, Vietnam, a small town he first visited in 1995. Back then, travellers were few and far between, but he remembers meeting an American backpacker who told him he liked doing drugs at Disneyworld. His mantra was: “Disneyworld on acid, better than the real world”. …..