In the morning light, yoga-clad tourists on vespas wind their way through the traffic in Ubud. We are in Bali, in the centre of cultural tourism. Surprisingly, many are young blonde women perfectly dressed and made up in Lululemon yoga outfits with yoga mats under their arms. It feels a long way from the slightly trashy, sour-smelling traveller destination that Ubud was 35 years ago when I was first here. It’s even further from when the hippie generation went to Asia in the 60s and 70s to absorb the culture of the Orient, and embrace its aesthetic ideals. But despite new stretch pants, it’s still orientalism. Even if the clothes don’t fit the environment well, the essence of the place and the Hindu aesthetics that comes with it match the intended inner travels of the modern yogi to whom a comfortable and safe space close to avocado-studded sourdough rolls and fruit juices matters as much as any transcendental mindspace. A safer, easier and more fashionable alternative to the equally Hindu birthplace of yoga in India, which still caters for the hardcore.

The Yoga run mainly takes place on the outskirts of Ubud, in what was not too long ago small kampungs – villages – nestled comfortably in the rice paddies. Today, the villages are all connected by an endless row of hotels, villas, and homestays. Overall, this tourism is tasteful, and the new establishments go to great lengths to construct buildings that fit into the environment, both nature and culture. Yet Ubud, as the original “homestay destination”, has been considerably watered out. Diluted. Dotted between homestays and hotels are restaurants serving burgers, pizzas, and coffee shops with skinny lattes, cream cheese croissants and their vegan siblings. The warungs, the traditional eateries, are far apart.

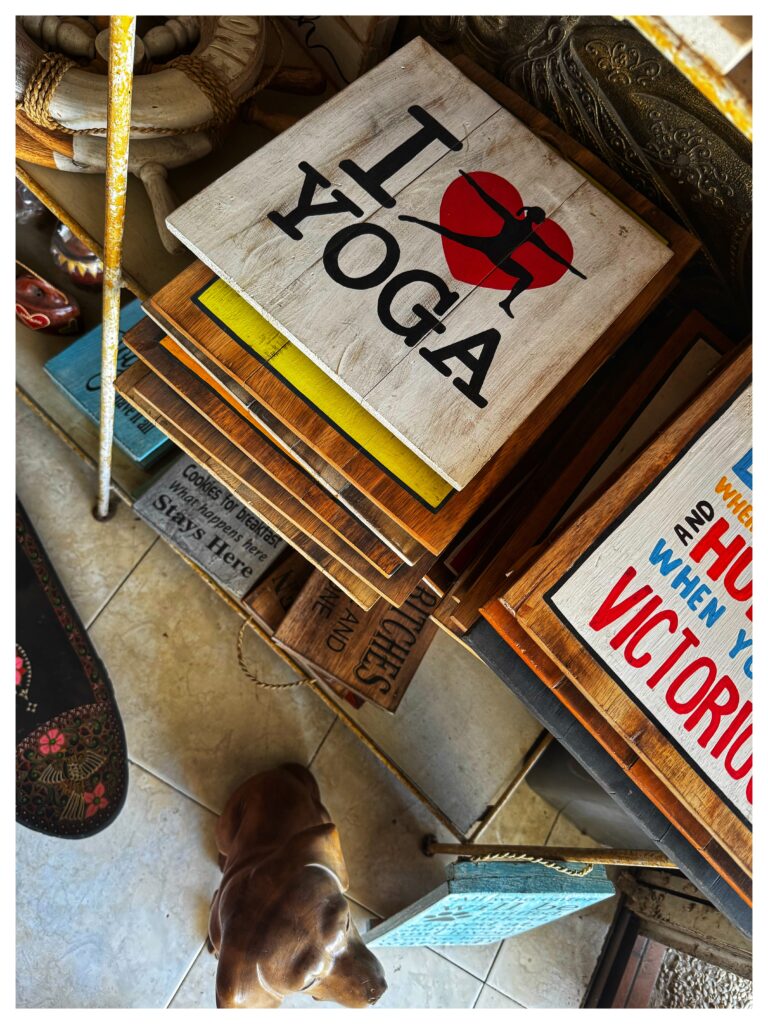

The heart of Ubud is yet another story: Nestled around temples and traditional houses–yes, they are still there–are the suffocating shops of high-end brands. The surf brands, even though Ubud has no beach, adventure brands, yoga brands and all the more dressy stuff. The boutiques aim to look classy, but end up tragically out of place next to an ancient temple. Or to perhaps be less critical: their solid Western aesthetic renders an interesting contrast to traditional Ubud.

If the yoga crowd of the Ubud outskirts seem to want to stop time to stay forever, it is the more typical tourist who reigns in the central parts. They buy “authentic” stuff at the market, visit a temple or two, probably feed the monkeys in the monkey forest, and consume a burger alongside fresh fruit juice in one of the many western restaurants before seeing a traditional dance show. Poolside, they gulp down a few sundowners overlooking a miniature rice paddy squeezed between the hotels to maintain the right Ubud experience. Tomorrow, they will head back to Kuta Beach to surf and sunbathe. They may navigate an easier cultural terrain than the yogis – or a terrain made for faster consumption. Still, all the same they are in Ubud due to their romantic orientalist ideas (otherwise they would have stayed poolside pissed in Kuta – Australian tourists start drinking beer already for breakfast).

Slow-moving yogis and more rapid cultural tourists: Are they not somehow lost in our images of paradise, looking for the anti-modern in the guise of ancient buildings or abstract ideas of finding harmony in an imagined cultural other, but ending up in an Lululemon or Rip Curl store? On Google Maps, locating a temple, just minutes later, munching down a slice of pepperoni pizza or a poke bowl.

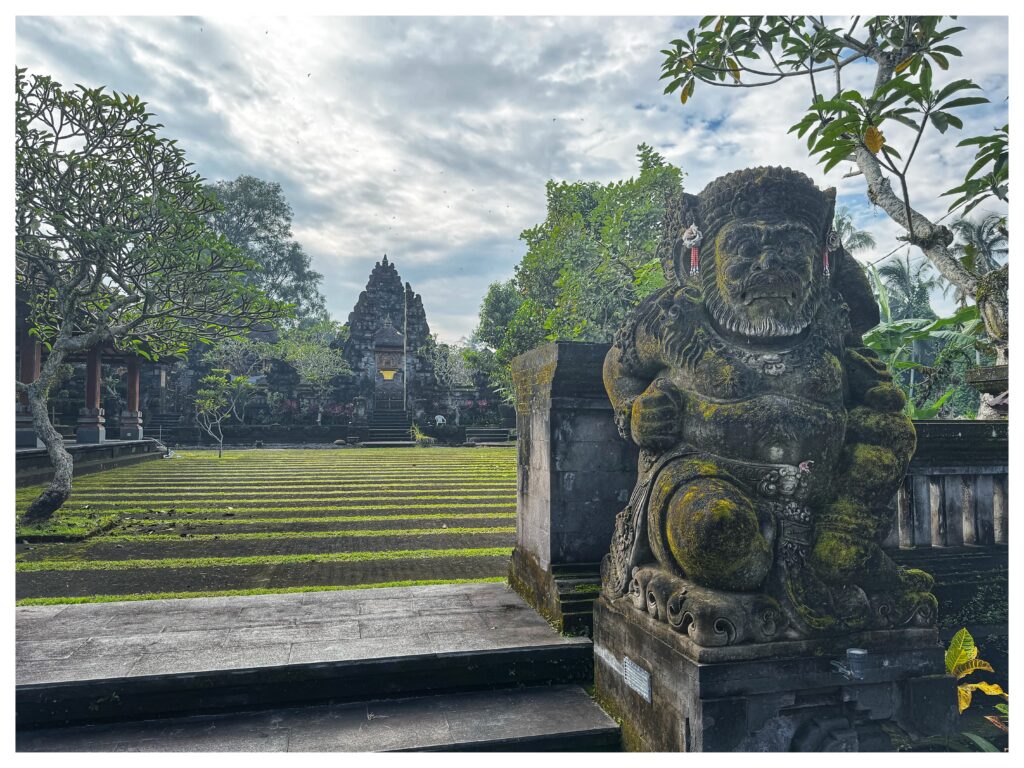

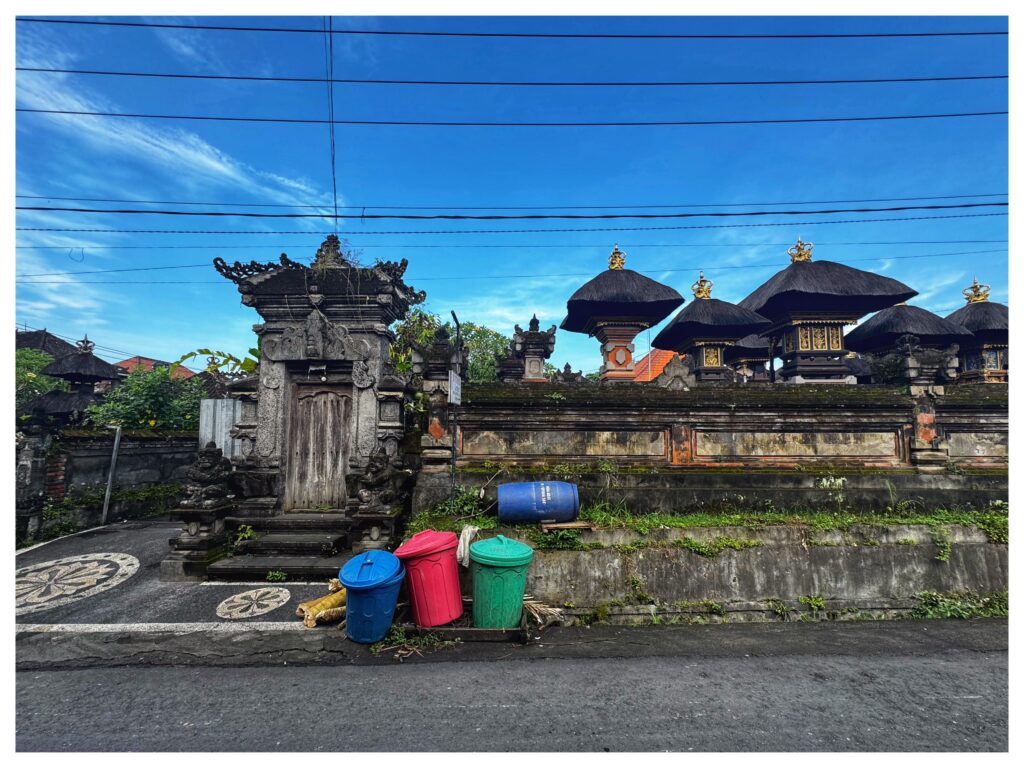

Ubud as an imaginary location is crucial, whether we are tourists on a temple run or part of the yoga “inner-self-help” industry. It is the realm of an imagined original culture, of temples overgrown by moss, where we hope to find what is lost within our culture or ourselves. We are the eastbound tourists, part of a mass trade.

My wife and I take a car out of Ubud to places where I, 35 years ago, walked for hours through incredible rice plateaus. Now there are houses. But next to a big parking area, constructed for people like us to get out of the car, there is a viewpoint, a place to overlook one of the few plateaus kept to please. That is to please the visitor. In front of it, there is a big sign saying I ❤️ Bali. It is almost impossible to get a picture of the beautiful scenery without it. It begs to be included in our “postcard picture perfect” version of Bali. In other places, they instead place large swings made of lianas, rattan or other natural materials in front of the rice paddies. All made for the tourist not to dwell in nature, but to get the perfect picture with nature, yet away from nature. I find it hard to imagine a more horrid image of agriculture than a dressed-up tourist in a swing in front of a rice field. It is an image that contrasts a “modern” self-image of the tourist in front and what we want to see as the distant agricultural past we have left behind.

Moving on in the lush landscape of Bali, our driver suddenly states, “We are leaving tourist Bali”, and then we are entering another realm. It’s a more mondain version of Bali. It’s less spectacular, but the black lava bricks of houses and walls are quickly overgrown by green moss. Moss grows rapidly here in Bali, perhaps allowing future tourism to spread further. If buildings look old enough, they have a weird lure for tourism, and for the future, there is even more imagined paradise to get lost in.