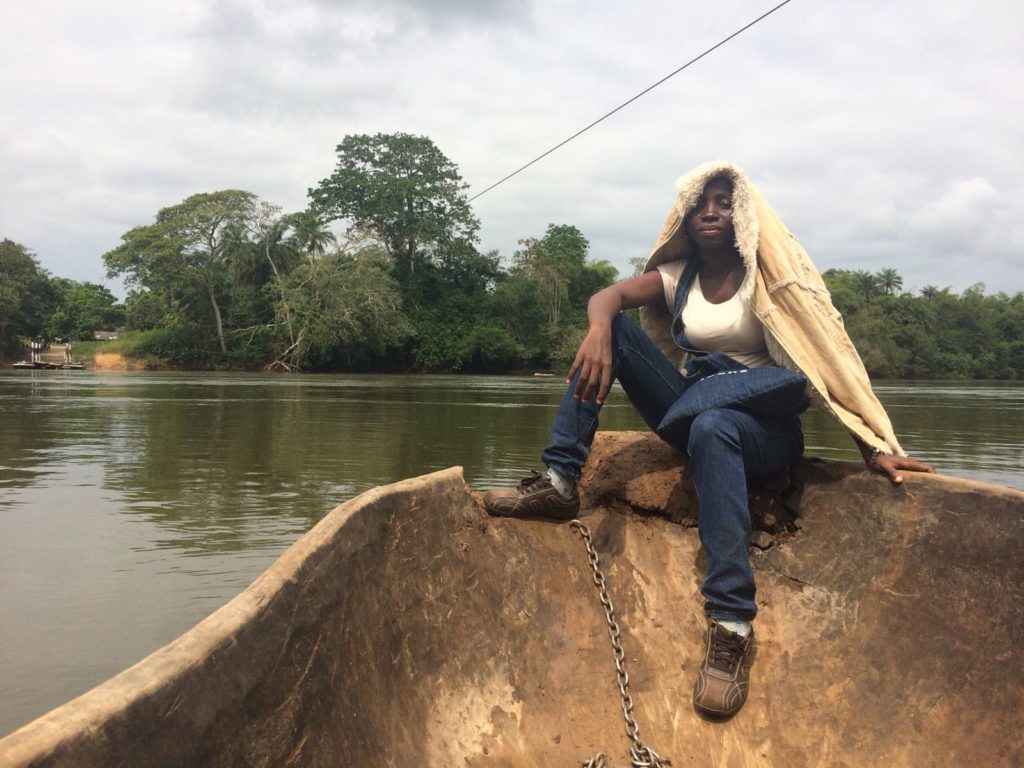

Photo credit: Deborah Bakker

I suppose that the first thing I did when I sat to write this piece probably underlines the problems we have in academia with emotions and fieldwork. Using my institution’s electronic library search, I typed ‘fieldwork and death’ into the search bar. The results were, predictably, disappointing.

In January 2018, eleven weeks into my twelve-week research trip in Northern Sierra Leone, one of the local researchers I was working with died. She died in the government hospital in Freetown, after a prolonged illness, the details of which are unknown to me. I was mid-breakfast when I got a phone call from Joaque, a man who had been helping me with contacts and access. I didn’t pick up the first time he called, because my mouth was full of bread, but when he called back immediately, I knew.

I want this piece to come flowing out of me, but it’s stuck in my throat like the bread I hastily swallowed as I picked up my phone. “We’ve lost Mafudia” he said.

The day before, I thought I had wrapped-up my project. I left the district town where I’d been for most of the last 11 weeks, and had my driver drop me off at my partner university for a seminar. The other local researcher I was working with, Osman, had come with as well, because we’d had one more meeting on the way back to the university. I’d hugged him goodbye, said that I’d see him soon. I’d meant it, I was already thinking of how I could come back to Sierra Leone. I didn’t mean that I would see him the following day, at a funeral.

I knew she’d been sick when we were working. Long days in remote communities made it clear that she was not well. I asked her every morning how she was feeling. The reply was always the same – ‘thank God.’ She took a day off and went to hospital once while we were working. I expected her to be out for a few days. I called her to say this. She was back the next morning. On several occasions, Osman and Joaque said that she was not well. That she had always been sickly. I assumed that if I kept checking in with her every morning, that she would tell me if she was too ill to work. I didn’t know what her illness was, and it’s not that I didn’t believe she needed medical treatment, but I never assumed that it was life-threatening, and I never pressed her. Just before Christmas, we finished the part of the project I’d hired her for, and she went into hospital two days later. A few days before her birthday. For the next two and half weeks, she was in hospital, first in the district town, then in Freetown. I called Osman. I called her daughter. The week before she died, everyone said she was improving. The doctors were pleased. I planned to stop in to the hospital in between interviews one day when I was in Freetown, but the visiting hours were later. I didn’t go back.

When we talk about fieldwork, the preparations, the joys, the challenges, the logistics of dealing with arranging meetings and dealing with transportation, and eating things you’d normally not eat, and hearing hard stories, no one tells you about how to go to a funeral for a person you’ve worked with for 3 months. No one tells you how to pick out the right kind of clothing, or how much money to give the family. No one tells you that there is no other experience you’ll ever have in field that will make you feel like more of an outsider than not knowing how to behave and grieve in the ‘right’ way. When we talk about coming back from the field, about readjusting and finding our footing again, and sorting through interview notes, no one talks about what to tell your colleagues who ask ‘how was it?’ There’s no good way to answer this when all you can think about is standing outside the boundary of the cemetery with the other women as your colleague, guide, friend, is buried, So, I didn’t really tell my colleagues – only the two who I’m really close to, and my supervisor. As for the rest, when they ask ‘How did it go?’ Any problems?’ I say ‘It went well! I have so much data.’ The words almost get stuck in my throat as I rush to get them out. Mostly, no one talks about how all of this will leave you with feelings of guilt so intense that in some moments, you cannot think of anything else – What if I’d insisted that she go to hospital earlier? Or insisted that she was too ill to keep working? Or paid to have her admitted to private hospital? Or? Or? Or…………

Weeks later, I went to give advice to a colleague’s project team about how I’d dealt with the university’s finance office and logistics and receipts. One of her PhD students raises a great question – in light of the university’s policy that research assistants have to have university contracts, what is the university’s policy about liability to our hired research assistant? I’d expected questions about these contracts, and so I’d brought my copies. When he asked the question, I was looking at Mafudia’s handwriting on her contract. I covered it with another piece of paper, lost my voice, and struggled to get out that the university had no liability, but that we had a responsibility to think of what our own moral liability was. Feeling obligated to explain my spluttering, I told them briefly what had happened, and then left.

My guilt, my feelings of obligation – to her family, to academic discussions about fieldwork – are tangled in my project. I feel pressure to get publications out as soon as possible so Mafudia wouldn’t be disappointed – or so I can tell Osman that I’ve kept my word. But reading the interviews she conducted is a struggle. I can hear her voice in the notes she took at meetings. And then I feel guilt for feeling so upset – I am not her daughter. She was not my daughter, sister, wife. I am not grieving in the right way.

At her funeral, I sat – straight-backed – in a borrowed shirt, by hair tightly wrapped in a scarf. I dug my nails into my palms. I bit the inside of my mouth, set my jaw, curled my toes into balls in my shoes. I was not supposed to cry. I started to cry a few times – and was told (kindly) to ‘bear it up’ because it was God’s will.

Some kindly American missionaries drove massively out of their way to drop me back in the district town after I got the news in the university. I’d packed a bag in 10 minutes – cash, phone charger, toothbrush. I don’t know what I was thinking about clothes, I left the university in a filthy t-shirt and stained pants. I had to borrow clothes when I got to the district town several hours later. Of all the things I could have brought that would have made sense, for some reason, rushing out of my room at the university, I’d grabbed the pineapple I’d bought the day before. I arrived back at the guest house I’d checked out of 24 hours previously, sweaty, not clothed for a funeral, and clutching a pineapple. Mercifully, it’s a small town, and Mafudia was well-loved, and I didn’t have to tell anyone why I was back. One of the cooks tied my hair in a scarf. There were so many small kindnesses – the barman took me to the funeral on his motorbike, the guesthouse manager refused to charge me, a woman I knew loaned me clothes, and the next morning, her husband dropped me to a major road junction so I could get shared transport back to the university. Two shared taxis and a motorbike – 4 hours crammed into the passenger seat of the taxi with another person, seat molding digging into my hip – exhausted – drained – felt like some sort of penance. That night, I told my mom what had happened. The guilt – of not doing more – of making Mafudia work too much – of not seeing how sick she was – of pushing her too hard – came out in sobs. My mom was so alarmed about my mental state that she emailed a friend of mine who’d spent a lot of time in West Africa and asked her to call me. When she called, I felt like I could finally explain to someone who understood – that a research assistant is never just an employee or colleague – but that they become, for a time, the person you trust most in the world. The intensity of the relationship cannot be brushed off. She told me that if the same thing had happened to her when she’d done fieldwork, that she would feel the same guilt. That I wasn’t guilty, but that my feelings of guilt were legitimate. My feelings of guilt are legitimate.

I am not guilty of causing Mafudia’s death.

There is nothing in any training for fieldwork that prepares you for this. Over the years, I’ve had excellent conversations, mostly informal, about how fieldwork training is inadequate, how emotions play a huge role, how fieldwork is hard. None of those prepared me for this. My friends and colleagues – the ones I’ve told – have been kind and supportive since I’ve been back, but I have this enduring feeling that something needs to come of this that creates a space for academics can talk about death in the field. I know that I cannot be the only one who has had this experience, and I cannot let this slide without forcing a broader conversation about our moral liability, Maybe if I’d have this conversation before, I would have given more thought to how to offer private hospital admission to Mafudia, or I would have insisted that the whole research team take a few days off. Maybe this couldn’t have changed anything, but I also feel like I owe it to her to say her name, and talk about her death.

It’s been a year now. Sometimes, I collide with a thought about Mafudia like I’ve walked into a wall. Once, it was walking into a grocery store and seeing a woman with a look of intense concentration that reminded me of her. Just before Christmas, I was out for a run and realized that it had been exactly a year to the day that I’d last seen her, and the thought stopped me in my tracks. I know that these are feelings that anyone could have when dealing with loss. These feelings are not about emotions and fieldwork. But they also are, because I can’t find the precise place where the personal breaks from the field.

The questions I have for myself now are mostly about Mafudia’s daughter, and what if, if anything, I can do for her. Mostly, I’m grappling with why I feel like I need to do something. If I offer to pay for her school, am I doing it to make myself feel better? If doing something makes a material difference in her life, does it matter why I did it? How are my feelings of needing to do something tied up relations of race and colonialism? If I think about this in terms of ‘responsibility’ to her, it feels patronizing, and if I think about it in terms of ‘debt’ – to Mafudia – is that better or does it imply that at some point the ‘debt’ is repaid? Or maybe my feelings about this don’t matter, and what does matter is that I could be in a position to contribute financially to the daughter of someone I cared about? These questions get tangled in other questions about doing fieldwork – about how it can be done with justice and human dignity at the forefront, and also, if this is enough.

I don’t know if writing this is right, or if I have dislodged the right words from my throat. I don’t know if it is too self-centered or too introspective or too much of rambling narrative. I do know that Mafudia was kind, hard-working, strong-minded, independent, and cared deeply about the rights of marginalized people in her country. She worked as an advocate for prisoners, for human rights, she took testimony from survivors of the war during the truth and reconciliation commission, she was so well-loved and admired, there were hundreds of people at her funeral, and you could feel the grief cutting through everyone. She helped people wherever she went but never took shit from anyone. I know that the world is better place for her being here, and a worse place in her absence.

Caitlin Ryan is an Assistant Professor at the University of Groningen. Her work focuses on gender and land deals, and the Women, Peace and Security Agenda.

Sierra Leone has a new president. And despite being challenged prior to the elections, the two party-system dominated once again. After two five-year terms under Ernest Bai Koroma of All Peoples Congress (APC), the second giant, the Sierra Leone Peoples Party (SLPP), takes over again. Julius Maada Wonie Bio of SLPP defeated APC’s Samura Kamara by gaining 51.8% of the vote in the runoff on March 31, 2018.

Sierra Leone has a new president. And despite being challenged prior to the elections, the two party-system dominated once again. After two five-year terms under Ernest Bai Koroma of All Peoples Congress (APC), the second giant, the Sierra Leone Peoples Party (SLPP), takes over again. Julius Maada Wonie Bio of SLPP defeated APC’s Samura Kamara by gaining 51.8% of the vote in the runoff on March 31, 2018. It is our pleasure and privilege to introduce a special issue of

It is our pleasure and privilege to introduce a special issue of