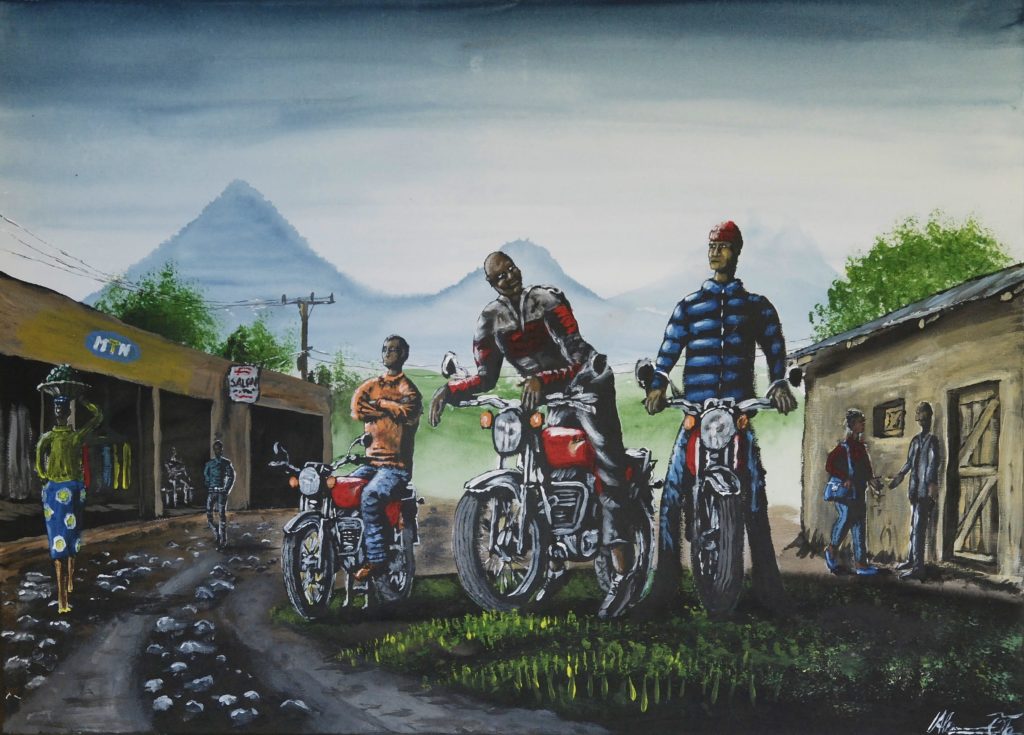

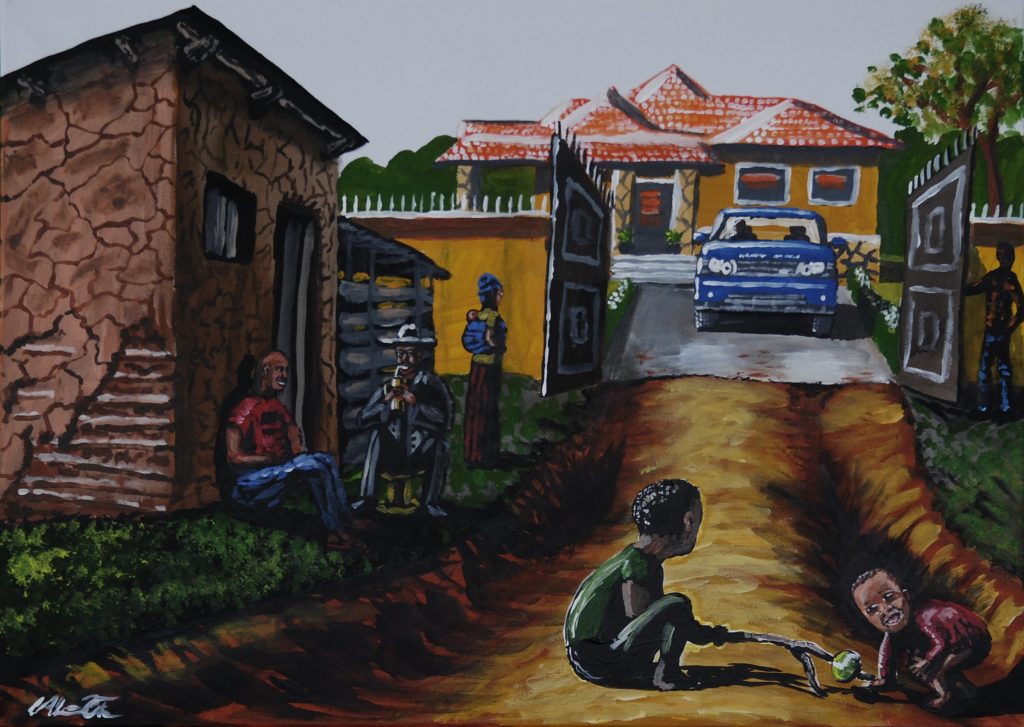

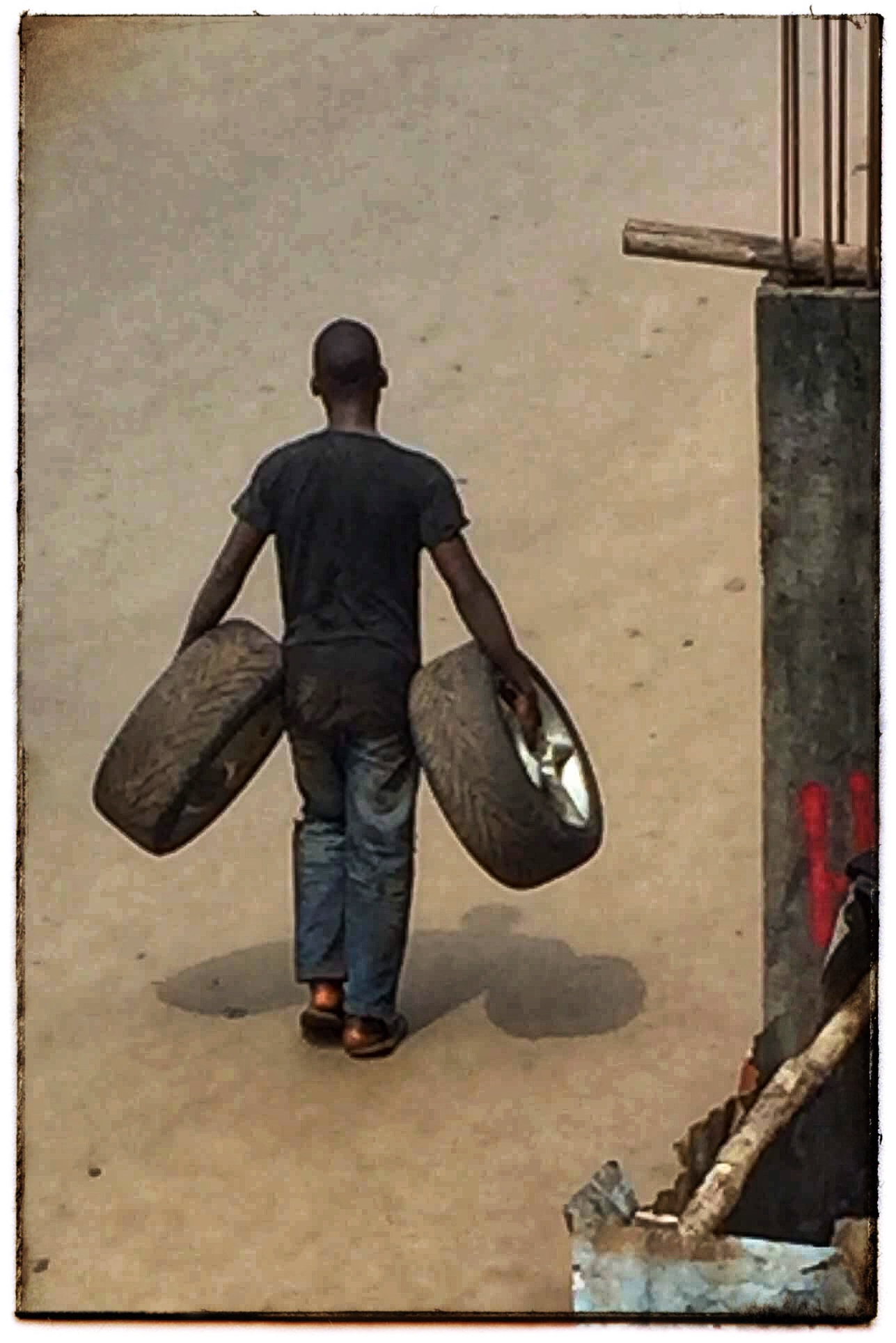

MOB – Members of Blood together with 103 a constituency number is an indication of the politics and gangs nexus – photo by the author

One Friday afternoon, they trickled in. One by one. Young faces with scars, tattooed, waving handkerchiefs and wearing coloured wrist-bands. We met in a concrete hideout constructed as a visible sign of one gangs’ ´mediation´ in a land-conflict – making sure that whoever would end up victorious would have to make arrangements with them. It was a surprising week, where I had accidentally stumbled upon a senior gang leader, hung out with him, and who – no doubt in an attempt to raise his own profile – called upon gang-leaders from all over Freetown to meet me.

On these pages, it was Kieran Mitton who first highlighted the significant presence of gangs in Freetown. I accidentally stumbled upon them as I probed into Sierra Leones politics and encountered multiple links between politicians and gangs. (1) To me it has become clear that Sierra Leone has indeed developed a gang problem. Sierra Leone like other West African countries continues to face a youth bulge and rapid urbanization. Evidence suggests no direct connection between a youth bulge and gang emergence – there is too much individual variance – Pollard 1999; Howell & Egley 2005 – but Sierra Leones various social problems impacts many youths in Sierra Leone and allows gangs to grow. Moreover, gang emergence is a problem as political competition is increasing in Sierra Leone. Post-war decentralization attempts have reproduced political competition at many levels and there are tensions between SLPP or APC especially after the transfer of power in 2018. Hence, the demand for violence and the supply of violence has increased.

Yet, we presently know very little about Sierra Leone gangs; how are these gangs organized? And how do they compare to other sodalities in Sierra Leone? In this post, I present some information on the organization of the gangs and argue that they are in three ways somewhat different from earlier sodalities; their organization, their rejection of patrimonial debt-relations and their embeddedness in society. While not meant as a systematic comparison, I posit Sierra Leones new gansterism against historical sodalities; youth groups in the 50s and 60s (Banton 1957; Rosen 2005), the rarray-boys of the 70s and 80s (Abdullah 2002), the armed groups in the war (Peters 2011; Hoffman 2011), and the post-war phenomenon of ‘youth-crews’ (Utas 2014) and party-taskforces (Christensen & Utas 2008; Christensen 2012).

Gangland Sierra Leone

Sierra Leone has three main cliques. The oldest and largest gang is the So So Black (Black), the youngest is the Cent Coast Crips (Blue) and their main rivals are the Members of Blood (Red). Gang members are recognized by a red/blue/black muffler (bandana) and most commonly a set of tattoos as identification markers. Members of Blood (MoB) have SoT (School of Thugs) and Blacks KKK (Keep the Secret) tattooed on their fingers or arms, sometimes alongside the number of their constituency. Older gangsters still have ‘BBM’ tattooed on their arms which refers to the Black and Blue Movement (BBM), when most Cent Coast Crips were still part of the So So Black.

Gangsters can also be identified by two other labels that crosscut them: Gulley (green) and Gaza (yellow). Those originating from Gulley hail from the seaside slum-areas such as Kro-Bay, Susu village (Aberdeen), Funkia (Goderich) while Gaza’s are ‘uptown niggez’. There is a subtle judgement in these terms; living in Aberdeen village at less than 100 metres from the sea I assumed that I lived in the ‘Gulley’ but one of the local MoB-hoods I live and hang-out with was adamant that they were ‘Uptown-Gaza’ rather than ‘Stinking Gulley’. Hence, Gulley vs. Gaza is a socio-economic judgement that is largely inconsequential; in gang feuds only the Red, Black and Blue matter. Almost every hood in Freetown can be mapped in one of the three gangs and the Gulley/Gaza label.

Similar to war sodalities (Richards 1996) and post-war street-crews (Utas 2014) gang-names are assemblages of western/global icons. The Red (Flag Movement) and Black (Leo) were imported by two US-based Sierra Leone rappers LAJ and Kao Denero. (2) They seem to be loosely based on the Los Angeles rivalry between the Bloods and Crips (where the Crips have both blue and black as colour). The word cliques is likely a direct reference to Clicas or hoods in Latin America. The terms Gaza and Gulley stem from the (hugely popular) Jamaican gang scene – it is common for cliques to give you detailed histories on Jamaican gangsters and their feuds.

Gangland Sierra Leone should not be viewed as a Freetownian phenomenon (just like the rarray-boys were a country-wide phenomenon – see e.g. Abdullah & Muana 1998). There is a gang-presence in the whole peninsula (e.g. Tombo, Tokeh and Sussex) all major towns (Koidu, Bo, Kenema, Makeni, Kabala and Kamakwie) and strategic rural places such as border checkpoints (Kabala, Kambia). Some towns in the provinces have own gangs, such as the Green Flag Movement in Kambia. A prime reason for upland presence is refugee for gang-retaliation after ‘tjukking´ (stabbing) somebody. Consequently, cross-country links between gang leaders of the same colour are very well developed and leaders in Freetown are involved in political tensions across the country as their members are hired. In ‘the provinces’ the Blacks are by far the largest with the Red only hailing the majority in Kamakwie.

Organization and control

Gang organization into large hoods, commanders, and varying degrees of hierarchical and centralized control set the gangs apart from the more loose organizational structure of previous urban sodalites like the rarray-boys of the 80s and the red-shirt and palm-attire groups of the 60s (Rosen 2005). Present gang-structures seems more akin to the direct war experience where groups were formed around strong commanders and varying degrees of informal centralized command (CDF: Hoffman 2007; RUF: Peters 2011).

Gangs are organized into ‘hoods’ and ‘sub-hoods’ (except for the Blue who are a ‘society’). The So So Black for example have a few very large hoods (E.g. G-State, P.H., C.W.H.) and each contains a number of smaller hoods. The smallest sub-hoods have around 30-50 gangsters and the large ones at least 400 to 500 members (men and women). (3) Sub-hoods emerge in one of two ways; a) by command as the leader of the overall hood rewards rising members with an own crew; b) self-organization by a powerful person creating his own team and later aligns himself with a colour. The organization into sub-hoods leads to the dazzling variety of names and the sub-hood structure may be a ‘compromise’ with the fluid street-corner boy organization immediately post-war (Utas 2014).

In general, most large Black hoods are in the east, Blue societies in the Centre and Red hoods overall in the West. Yet there are so many exceptions that it is at most a general statement of dominance and certainly not a real presence, e.g. every colour has numerous teams across the city, there is a prominent Black-hood around Lumley-Carwash, Funkia and from Ogo-Farm onwards (hence in MoB/West territory) and by the same token MoB controls Brookfields, Kroo-Bay and parts of Lightfood Boston Street (all central – Crips – areas). Gang members cannot travel to areas controlled by others, unless they travel with Jew-men (‘fences’ for stolen goods), white researchers, politicians or when they are famous and/or have connections (which only holds true for a handful of gang leaders).

Within the hood, gangs are hierarchically organized. There is some variation but the general model is that hoods are controlled by a CO (commander) with 50 (or 5-star), 4gen, 3gen as statuses of decreasing importance. Around the CO is a team with authority, with a Godfather (the key advisor), Chairman (chairing meetings), Brigadier (muscle), Beef-King (muscle for intergang fights) and Bouncer (clearing the way for the CO in large crowds). The CO is the most powerful – initiation, the type of operation and promotion are his exclusive right – but he generally takes most decisions in collaboration with the Godfather. The 5, 4 and 3 in 5O and 3/4Gen are claimed to refer to the number of major offences committed, but older members say that 5-start is awarded after a kill, meaning you need ‘only’ one offence. (4)

The three colours differ most notably in their extent of centralized control. Gangs do not have a central command although overarching gang structures do exist. The power to command many goes to ‘informal’ leaders who get their status from controlling very large hoods, a long history in the gang (all COs I spoke to claim to have over 15 years of ‘experience’) and ‘connections’. The So So Black are the most centralized; the leaders hold positions in the overall ´EastHood´ can issue orders and mediate in intra-gang fights. The Blue and Red have ‘CentCoast’ and ‘EastCoast’ as overall label but lack centralized control. The Blue have emerged out of a power-struggle within the Black and Blue Movement and the constant threat from the Red. Since 2010 the Blue have had two informal leaders but the reign of each was short (one was killed, the other fled after a stabbing). At this moment in time, overarching control is limited. The MoB finally are the most split and have internal power-struggles. The best-known faction is the ‘Brookfields’ hood while other strong hoods are around Mount Areol (the Mountain cut area) and ‘BlackStreet’ (the Stadium area).

Big men, debt and the last day

Perhaps the best reference point for comparing the cliques phenomenon is Mats Utas’ work on street-crews after the war (Utas 2014). At that time, many youth harboured feelings of exclusion after being used during the war and now losing out on the peace. According to Utas this lead to a new imagined community, a ‘rarray-boy nation’, where street-crews played their ‘game’ against the ‘system’ and simultaneously sought integration within it. I’m neither trained as a sociologist or an anthropologist, yet based on ten months deep hanging out with cliques I think the clique-game is very similar to the one described by Utas. Yet, there are two main differences: 1) unlike the rarray-boy nation, cliques have very few links with big-men and; 2) they demand direct pay rather than develop extensive debt-relations.

Youths in Sierra Leone typically seek to develop patrimonial relations and sababu (connection) in search for work. Violence is governed by the same similar principles. Enria shows that youths within the political parties are bound by patrimonial relations; their loyalty to their big-men is described as love (Enria 2015). Christensen and Utas (2016), argue that party task-forces, seek protection from big-men in their attempt to find jobs and engage in work that leads to lasting debt relations that bind big-men and followers. This modus operandi is similar to the groups in the 60s and 80s (Banton 1957; Abdullah 2002) and continues todays in the form of political party task-forces. For example, in one ‘solda’ team Group. (5) I hang out with have received everything they own (Money, cooking-pots, a coleman, thee-can and storage bags) by big-men from various political parties, offices nearby and businessmen. The group has campaigned for nearly two years expecting jobs and get-out-of-jail cards. After elections, little is given yet they remain loyal to the party. The group is a typical example of love (and betrayal) and the lasting debt relations that bind big-men and followers.

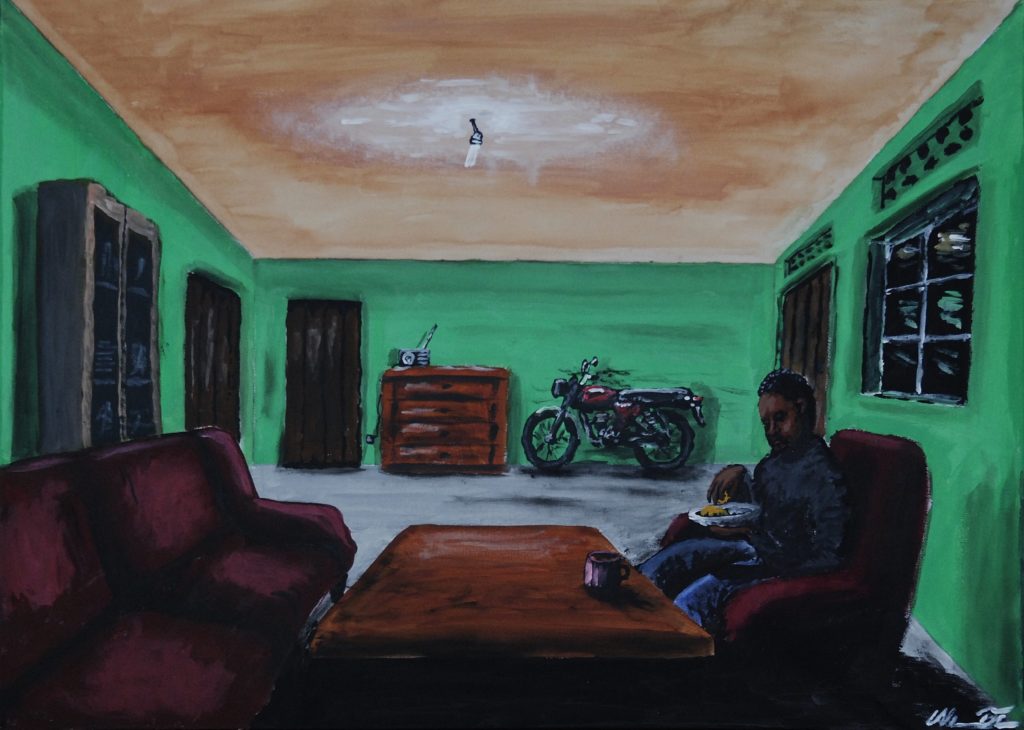

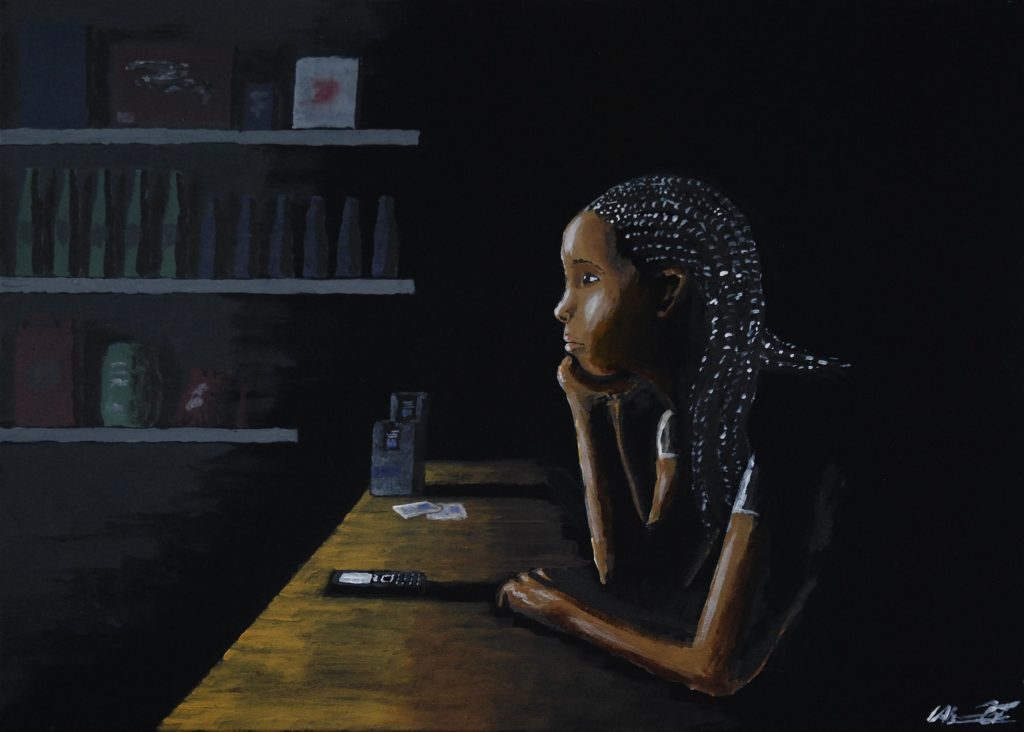

It seems that the gangs are different. First and foremost, cliques are governed by direct pay rather than debt relations, as is particularly clear from the way they conduct their ‘economies’. Many gang members actually ‘work’, hustling in the informal economy during daytime – operating at carwashes, carrying loads, manning roadblocks, doing casual jobs and cleaning. As this income is generally minor, gang operations are used to top-up income and/or to cover for large expenses (I have met various gang-members who pay their college fees through gang operation). Younger members, engage in pickpocketing and purse/bag grabbing while the older ones take part in robberies. (6) Burglary is generally viewed with disdain (‘for thieves’) as it does not require ‘heart’ – but it is grudgingly allowed by COs when the ‘gron dry’ (there is little money going around). Daylight robbery is most appreciated; you directly take what you want knowing that no one can challenge you. (7) It is an immediate economy that satisfies instant needs.

The absence of patrimonial relations and the requirement of direct pay are particularly pronounced in the gangs relationships with big-men. Except for leaders with extensive political connections (see a forthcoming post) there are very few patrimonial relationships. I have found some links between cliques and some nightclub owners and businessmen (e.g. Med Keh, Sanusi Buski, Washing Guy). Yet, in the rare instances that these connections exist, dependency relations are absent. There are occasional patrimonial exchanges (e.g. paying bail) and are mostly restricted to COs (e.g. with separate evenings on which they get free drinks). For example, at one point in time a journalist was beaten up for reporting on frequent burglary, in a hood that I frequent. One big-man who owned the outlet, suspected the gang demanded an explanation from the CO. Yet he was cursed and told that he could never inquire about these affairs after which the big-man paid 50.000 Leones to the CO (which was in turn refused). (8) As a forthcoming post highlights, the exchange between clique-leaders and politicians is also based on direct pay (in a lump-sum and in a limited number of cases ‘per diem’) rather than promises of jobs. Gangs themselves refer to their alternative order as the ´last-day’; an individualized ‘end-of-the-world’ concept where you now take what you need.

Embeddedness in society

I’m closing this post with a final observation. As I just argued, the cliques can be read as a partial rejection of patrimonial relations (similar to the RUF, see e.g. Richards 2005) and society (just like Utas’ post-war rarray-boys). Yet, unlike the inward-looking RUF that enclaved itself from 1993-1996 (physically) and later mentally from society, todays gangs are situated within society. A prominent testament is that gangs generally have good relationship with the neighbourhood; many members (though this depends on the hood) are son-of-the-soil, most crime is performed outside of own hoods and gangs provide security against roaming cliques and rarray-boys. At one point in time, 7 gangsters (‘mercilessly’) beat up a boy and stole in his phone. Yet, as the crime was committed in his own neighbourhood, the CO ‘arrested’ the guilty members and put them in police-custody for one day. Demonstrating the social standing of the gang in the neighbourhood, the mother of one of the gangsters came in crying, begging for her son’s release – which was subsequently arranged by the CO with the local head of police during a gang football match. On another occasion, I witnessed the spoils of crime being shared with family members and dependents. Of course, there are difficulties in that the community may not want the security that is provided, complaints about the need for it to happen (as the gangs are themselves a major cause of crime) and family members in the community accusing their sons (and daughters) ofbeing idle and lazy. Yet, every hood that I hang extensively hang out with has tight connections between the local sub-hood and the community.

A second indication of the embeddedness of the cliques in society is the relations with the secret societies (Ojeh, Odelay, Hunting and Padul). For example, both the CO and the head of police in the previous examples were Agba’s (leaders) in neighbouring Ojeh’s. Moreover, the vast majority of gangs are a member of these societies. For example, the main base of the Crips is literally between one of the largest and most political Ojeh’s in town and a very political Hunting Club-House (it is the only clique that I am aware of that has stronger ties with big-men from the secret-society than with political big-men as evidenced by the fact that most of the money comes from the society rather than politicians). And perhaps, most telling: when I had my first meeting with all those COs and 5Os at the invitation of one of the leaders the cliques spoke Yoruba, a Nigerian language used in Ojeh.

Hence, unlike the Rarray-boys pre and post-war as well as some inter-war sodalities, it seems that the current gang-scene in Freetown is more embedded in society than previous sodalities. In fact, it is this embeddedness that could prove to be the ideal entry point for policy-makers. It is clear that repression is not the best way to address problems involving gangs. Yet, what approach should be taken in tackling the clique-problem without repression? As the next post that I will write on this forum shows, politicians have been trying to reduce the social violence and have engaged with most of the current gang-leadership. Yet, the effect has been that leader positions have been strengthened and the appeal of cliques has increased. Perhaps a better way is to tackle the clique problem with an indirect approach; improve societal structures with an appeal to cliques so that they can be dislodged without strengthening existing clique structures. In fact, as everyone who interacts with cliques and their leaders will testify: without exception they want a way out. Addressing real youth needs through societal channels seems to be a promising direction.

Kars de Bruijne is a Postdoctoral Research Fellow at the University of Sussex researching Sierra Leone politics, hybridity and incentives for violence. His PhD-research (University of Groningen)looked at the role of mutual optimism for political and military decision-making in the Sierra Leone conflict based on fieldwork between 2012 and 2015. He is also a research fellow at the Clingendael Institute.

Endnotes

(1) I undertook research in the country for ten months and extensively hung out in six hoods.

(2) LAJ formed the Red Flag Movement – out of which the MOB emerged whereas Kao Denero headed Black-Leo.

(3) With about 200 hoods belonging to the Freetown EastHood (Black)means that the blacks may have a membership of (at least) 6,000 members in Freetown. With the Red and Blue gangs and presence in the interior it seems likely that the absolute lowest membership is somewhere around 10- to 15,000.

(4) It remains hard to verify these claims.

(5) An informal security provider attached to a political party (the groups described by Enria)

(6) A nation-wide ban on guns after the war meansthat armed attacks are manual and either take place with a ‘punch’ or with a ‘chopper’ (knives/scissors/iron bars).

(7) Note that gangs no longer really engage in the flourishing drug market. Ganja farming is operated by separate ‘Cartels’. Previously some gangs were involved in the cocaine trade but the highly secretive nature of this trade means that gangs can no longer be bought.

(8) Note; the gang was not responsible for this particular beating

Sierra Leone has a new president. And despite being challenged prior to the elections, the two party-system dominated once again. After two five-year terms under Ernest Bai Koroma of All Peoples Congress (APC), the second giant, the Sierra Leone Peoples Party (SLPP), takes over again. Julius Maada Wonie Bio of SLPP defeated APC’s Samura Kamara by gaining 51.8% of the vote in the runoff on March 31, 2018.

Sierra Leone has a new president. And despite being challenged prior to the elections, the two party-system dominated once again. After two five-year terms under Ernest Bai Koroma of All Peoples Congress (APC), the second giant, the Sierra Leone Peoples Party (SLPP), takes over again. Julius Maada Wonie Bio of SLPP defeated APC’s Samura Kamara by gaining 51.8% of the vote in the runoff on March 31, 2018.