By January 2019, politicians were recruiting gang members once again, nearly a year after the Sierra Leone elections. They were asked to join in protest against the decision of a commission of inquiry to go after prominent political figures. Rival politicians, however, tried to shift gang allegiance and used an informal intelligence network to single-out, beat-up and warn potential troublemakers. By the end of the month, I spoke to one senior politician about how his party seemed to lose control over the cliques (the local name for gangs). The talk alternated between refusing to talk about cliques and him showing pictures of Commanders (COs) and so-called 5Os whom he had supported in college, bragging about how they accompanied him during rallies and boastings about how he still could command them still given his leading role in the secret society. Politics and gangs in Sierra Leone are closely intertwined.

In this post I explore the relationship between politicians and cliques: why, when and how do politicians interact with the gangs? I consider three elements in the relationship between politicians and gangs: attempts to engage in “peace-making”, the role of cliques in elections and finally the role of Sierra Leone gangs outside of elections. Based on the evidence, I suggest that the growth in cliques is in part politically sponsored and I use the metaphor of a market to describe the present situation. Prior to the emergence of cliques, political violence in Sierra Leone was best described as a post-war “oligopoly”; a few big-men had extensive connections to former warring factions and their leaders. Today, the supply of cheap violence has increased but so has the political demand. Consequently, a “free-market” for violence has emerged.

Politicising peace

Violence is a common feature of Sierra Leone politics. Yet, many politicians are uncomfortable with the role of political violence in general and the role of cliques in particular. We only have to take a look at politics in the Western Area (Freetown, both urban and rural). In Freetown, attacks on political opponents, journalists and political allies Name: Mats Utas Title: Professor in Cultural Anthropology and Head of department Department: Cultural Anthropology and Ethnology How does your research contribute to a better world? (med cirka 100-150 ord): “Anthropology should have saved the world” says one of today’s leading anthropologists, but he goes on saying that this far we have failed to do so. Anthropologists understand what people do, not what they say they do. In my research I have studied child and youth soldiers. Some of my findings are radically different from what the western world wants to believe. In one case I hung out with ex-combatants for two years. I learned to know what they did and why they did what they did, which was not at all what they initially said they did. From the beginning they made up stories because they did not trust me. My research results were often at odds with general knowledge and it took a lot of time to convince aid-organizations working with reintegration of young ex-combatants to proceed differently with their work. I was certainly not alone. A whole group of researchers armed with similar results did it together. Maybe we didn’t change the world, but in our own small way we help to make the world a better place. are common resulting in a constant threat of (small-scale) political violence. Hence, senior party members in the area are expected to control cliques and other violent groups (often through a government sponsored role in the secret societies). Yet, I spoke to various persons who were ambivalent about having to resort to (cliques) violence for political survival. This fits in with my experience of Freetown; the vast majority of politicians do make small cash payments to cliques to maintain some influence and hire them during elections. Yet, from the side of the politicians these links are accepted as a necessary evil and are generally transactional and shallow.

Over the last ten years, however, a small group of politicians (around 20) have developed extensive relations with cliques. These relations were primarily developed as a result of politically sponsored peace-deals between the three gangs (represented by a colour; blue, black or red). The earliest traces stem from 2009/2010, when one minister sponsored peace between the then Black and Blue Movement and the Members of Blood (Red) after a killing in a nightclub. An organization was created with representatives of every colour and used for political purposes. A second attempt came a few years later when another politician set his eyes on becoming a minister and brought the three gangs back together. Being able to unite them was the prime reason for granting him a ministerial position and the ties were extensively used both in and outside of (party) elections (2017-2019). A third attempt to foster peace were various initiatives in 2017 and 2018 when another politician encouraged cliques to “come together”. Also, this third peace attempt became a political instrument as it ensured loyalty to the politician during the election and thwarted the opposition.

I started to realize how “threat to Peace” and “inter-gang violence” are also used by cliques to “demand” political patronage when I called “Dog-Chain” – one clique-leader. In the months preceding this call, I had developed extensive public ties with someone central in the above-mentioned peace efforts. But when I spoke to Chain he boasted that he was the one I should deal with; “I’m the overall clique-leader, I can command cliques throughout the country” and “I am the only one who can bring all colours together”.(1) Later as we sat down he confined that: “with N.N. (a prominent) politicians you can mess around”. Tell god tenki, that Sierra Leone is not El Salvador but I couldn’t help but think about how well-developed gangs like MS-13 and Barrio-18 discovered their political strength: “We dump bodies on the street until they say yes. And they always say yes” (Farah, 2018).

Electoral Politics: Playing the Game and Politics

It is helpful to make a distinction between “Politics” and “the Game” (see Utas, 2014) to better understand the relationship between cliques and politicians. For cliques, “Politics” represents the wider socio-political system while the “Game” is their hustling for livelihood, hanging-out and intergang beefing. The relation between the two is ambivalent. For example, one gang leader had the name of a minister tattooed on his shoulder but while showing the tat, told me how he despised politicians. Despite the ambivalence, “Politics” generally takes supremacy. This is perhaps best illustrated by the explicit and negotiated agreement that governed clique involvement in the past election campaign; early 2017 heads of the Blue, Black and Red came together in a meeting sponsored by politicians and jointly agreed that “the Game was off”.

This agreement (effectively freeing gang violence for political use) had two effects. First and foremost, it meant that all inter-gang beefing was forbidden – something that was violently enforced by gang elders who sponsored the deal. Yet it also meant, that every hood and some members were free to link up with the politicians of rival political parties. As a result, political units would consist of different gangs – e.g. Blood and Black, foes in “the Game” but now brothers in “Politics”. It also meant that members of the same gang (e.g. the Black) had allegiances to different political parties. Hence, they were friends with one another in the “Game” but enemies in “Politics”. Probing into this dilemma, I was told that gang hierarchies takes precedence; those higher in the gang hierarchy (e.g. a CO) would be allowed to campaign while those “lower” in the gang-hierarchy (e.g. a 5O) had to leave the area.

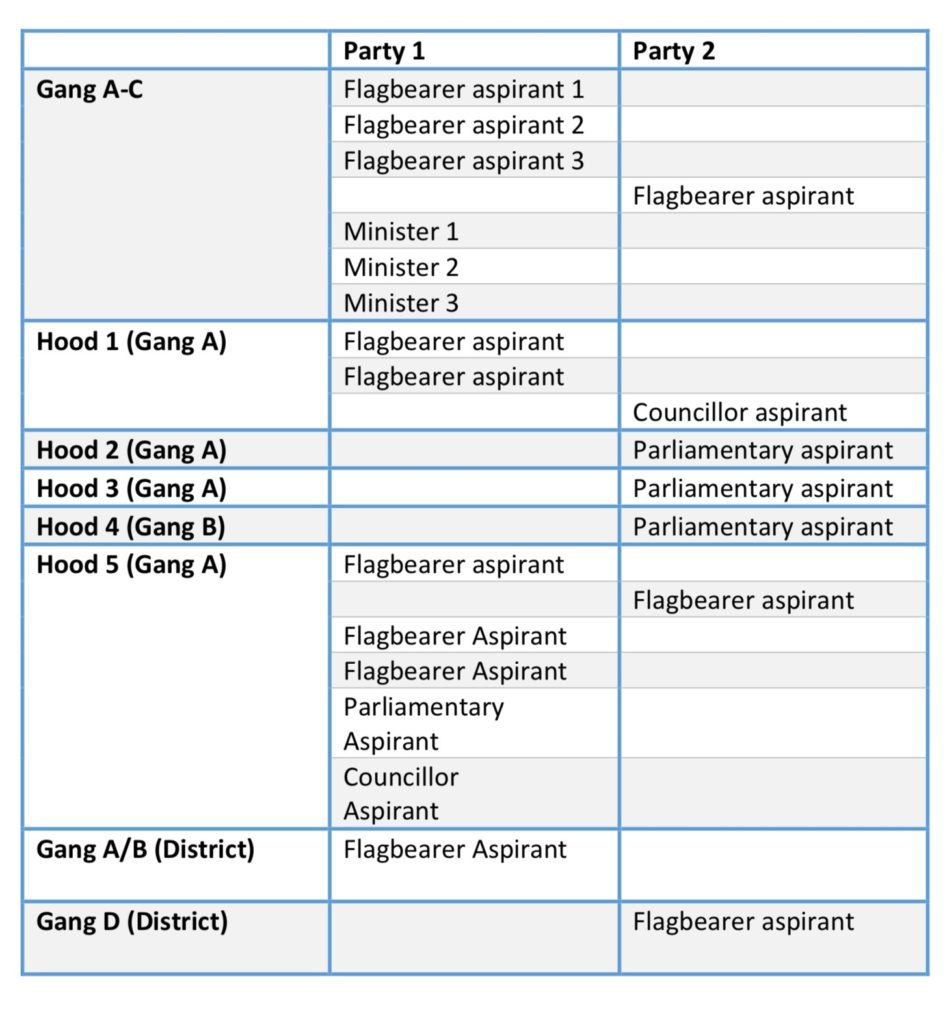

The agreement and previously developed ties, meant that the role of cliques in the past election campaign has been unprecedented (it is very similar to the 2006 deals that managed the political “integration” of ex-combatants, Christensen & Utas, 2008). Many politicians employed cliques for general protection, ability to hold rallies without disruption by opponents, have large crowds (cliques can and do call on many followers) and to influence voter turn-out. My more extensive work in six hoods as well as various one-time visits to other cliques tells me that politicians at all levels and from all major political parties have employed cliques; councillors, parliamentarians and presidential flagbearers (see table 1). The only difference between them seems to be the size employed. Councillors and parliamentarian use groups of around 15 to 20 while flagbearers go up to 50.

Cliques are for hire and expect to have direct pay (see a previous post highlighting how “direct pay” is the modus operandi of gangs). Except for some gangsters at the very top, payment is not negotiated. Prices vary but are generally low – at around 100 dollars for a month’s work or 2 dollars a day for a group (the lowest was 70 dollars for about 7 months to a group of 50 cliques by one politician aspiring to be the flagbearer of a major political party). In addition, candidates are expected to provide daily moral boosters (Pega and Maggi – cheap alcohol and Ganja). Promises of jobs or large sums of money after elections – or at least continuing favours – occur but do not replace immediate pay. There is massive disillusionment among cliques as to broken promises and internally many advocate a more instrumentalist approach in the future; more and daily pay. There are clear differences between cliques and other providers in the market for violence; ex-combatants do negotiate for their services, do not always seek direct pay but instead cultivate patrimonial debt-relations.

Political competition and the use of gangs

By March 2018, when the elections were over, most politicians left the gangs and “the Game” was back on. However, during my time “Politics” regularly took precedence over the “Game”. One time I hung out with a MoB hood when two busses with Blacks arrived to see the parliamentarian they had campaigned for. Their car-wash had been demolished. As rival gangs cannot enter one another’s territory, I expected a move by MoB but to my surprise they casually dismissed this intrusion into “blood” territory as “politics” (and they recounted stories of individual Black-members who had been “very strong” during the past campaign). This is one out of various examples where “Politics” overtakes or at least influences “the Game”. For example, gangsters that “make a name” for themselves in the centre are generally considered more successful than those that operate in the East and West of Freetown. The explanation for this is that the centre is the most political and being able to succeed in that environment shows that C.O.s (Commanders) are able to play against “the system”. Another is that becoming a CO – particularly a CO of a large hood – is generally only possible when having “political connections”. The connection ensures that the CO and those who are important for the gang are protected. The connection can pay or stand for bail, influence the court, amend the charges or provide income.

Hanging out with cliques and probing into the usage by politicians, I however discovered a more troublesome reality of the extensive employment of gangs outside of elections. For reasons of space, I limit myself here to horizontal politics (competition between politicians from the same party).

One way in which cliques are used is for ministerial positions and to stave off contenders in the party. I have specifically looked into the selection of one politician whose aim was to be promoted to a minister. Both clique-leaders and the politician told me how they first organized a public appearance with clique-leaders and the minister-to-be and later a private meeting to back his candidature. Soon thereafter the politician was appointed as minister by the President as it was understood he could control (and use) the gangs. In the years that followed, this access was used to stave off contenders through an ingenious clique-payment scheme. The rental accommodation of various prominent CO’s with family (of Blue, Black and Red) was paid for and on a monthly basis large sums of money were distributed among to individual COs (80 million Leones – around 8000 dollars). These COs in turn set up a rotating system for lower COs and 5Os (some would be paid every month and others on a ‘one month on one month off’ basis) reaching perhaps close to 300 prominent cliques members. The ministers control of the cliques has been used at various times to put pressure on contenders.

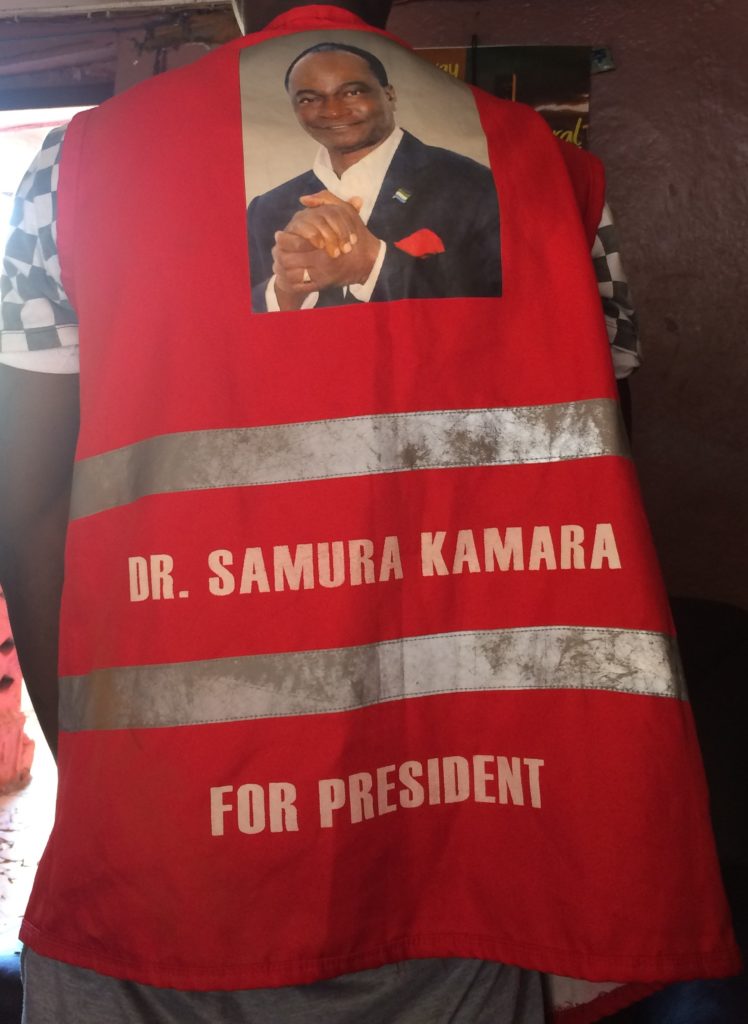

Another example of politicians using cliques for horizontal competition are the October 2017 elections for the APC leadership. Nearly all big-guns had vied to become the flagbearer of the APC and many had spent a fortune on their campaigns. However, a pliable candidate was imposed by the leadership and the former president was elected as Chairman-for-Life and the Party Leader “until death do us part”. There are various reasons for the ability of the APC executive to succeed in imposing people, but control over cliques played a role. I have confirmed, that in the days before the APC-convention large cash payments were disbursed to cliques to ensure their loyalty. At the convention, gangs engaged in threats and occasional violence against other contenders. Various flagbearer contenders confirmed that they felt under physical threat. Some contenders had equally hired cliques’ services. Yet, mechanisms like the aforementioned payment scheme meant that nearly all cliques were ultimately loyal to the executive and their middle-men. Hence, cliques were used for competition over the highest offices in the party.

These examples are just the tip of the iceberg of the usage of cliques; I have seen cliques being used to attack opposing internal factions as well as to ensure protection against too centralized executive (party) power. And cliques play(ed) a substantial role in inter-party tensions in the country. Cliques are therefore “capital” worth protecting. For example, in 2016 the then Deputy Minister of Defence started a “war” on cliques, carrying out massive arrests and declaring himself “the only 5O in the country”. Yet, a handful prominent politicians hid the most prominent COs and 5Os in Guinea and Liberia to weather the storm until the elections.

Political violence: Gangs and African politics

The example of hiding clique-leaders illustrates that the prominent role of gangs has not “just” suddenly emerged. Political demand for their services has sponsored their growth. There are a couple of reasons for this increased political demand. First and foremost, the geographic imprint of the war has had the effect of unevenly distributing ex-combatants over Sierra Leone’s two political parties with the majority of ex-combatants hailing from the South and East. In power the northern-based party could draw from a much smaller reservoir of ex-combatants from the disbanded army in 1998, some parts of the RUF, some Northerners and South-Easterners who had shifted-sides. Yet, compared to the south and east, the reservoir is smaller and ex-combatants are becoming older. Hence, it was strategically understandable that younger providers of violence – i.e. cliques – were recruited.

Increasing demand for the usage of cliques is not only a matter of replacing one group with another. A second reason is that Sierra Leone’s political order is increasingly generating demands for violence. Politics in Sierra Leone is simultaneously highly centralized and hyper local with the effect of reproducing Sierra Leones bifurcated party-order everywhere at the local level. Post-war decentralization – both reinstating the chieftaincy and decentralizing central state function – has led to a continuous contest over local power and corresponding pressures. As violence was often a tool in local contests (Rosen, 2005; Tangri, 1967; Christensen & Utas 2008; Utas & Christensen, 2016), more contests has simply meant more violence.(2)

Paradoxically a third reason for the higher demand for violence is the possibility of a democratic transition. Sierra Leone has a hybrid political order; informal subnational institutions perform state functions but are in turn co-opted by the centre. Democratic transition, however, means that not only the central state but also the hybrid political order has to change; heads of unions, markets, bikes, golf-clubs and student-bodies have been replaced. Studying the power-transitions of over twenty hybrid institutions has taught me that change-by-force or management-through-force is very common. Hence transitioning and sustaining this hybrid-order given the attempts of a strong opposition to return to power, generates a continuous demand for (clique) violence.

The increased demand for violence has had a major effect on the market for violence. From 2002 to around 2012, violence was almost exclusively regulated through oligopolistic principles; a limited number of ex-commanders controlling sizeable groups of ex-combatants and long-standing patrimonial relationships with some politicians. But the increased supply of clique-violence and the increased demand for violence has given rise to a free-market. In this free-market there is an abundance of available labour, many different groups offer the same product and are therefore unable to negotiate prices, there are lower prices (cliques are being paid less than task-forces), there is less brand-loyalty (cliques can work for different sides, sometimes at the same time) and there is also a larger number of buyers. In short, a free-market for violence has been emerging where buyers are king.

One should not be fooled. The emergence of this free-market is not just a by-product of failed social policies and the “unexpected” emergence of gangs (just as the reintegration of ex-combatants did not “just” happen). Rather, it is a market that is deliberate and politically sponsored. Sierra Leone is no longer a weak state in terms of its security – it has a strong and relatively well-disciplined military and a sizeable police force. Both have deliberately not been used to combat gangs but instead have been used to sponsor the cliques for example in conniving with crime or by providing gang leaders with a ‘get out of jail’ free card. Politicians have contributed to the growth of gangs through mechanisms like the payment scheme which has allowed gang-leaders to strengthen their position within the gang and ensures some form of income. As far as I am concerned, the political sponsoring is the most worrying part of cliques in Sierra Leone. Rather than addressing real youth needs, political elites have expressly kept the youth in a position of dependence and modelled a market for violence that fits their political needs; disposable and cheap violence for hire.

Kars de Bruijne is a Postdoctoral Research Fellow at the University of Sussex researching Sierra Leone politics, hybridity and incentives for violence. His PhD-research (University of Groningen)looked at the role of mutual optimism for political and military decision-making in the Sierra Leone conflict based on fieldwork between 2012 and 2015. He is also a research fellow at the Clingendael Institute.

Endnotes

- Despite tiring everyone in explaining that I was a researcher with no means to engage in projects, clique-leaders competed over contact with me, expecting future pay-back.

- NEC officials told me (confirmed through local data) that that the majority of (bye-) elections has been violent.