“Is Foday back home?” I asked Erik, a former Danish Superliga coach and owner of a second division club in Sierra Leone. “I don’t know where he is, he just disappeared, he didn’t make it to the flight from Denmark back to Sierra Leone.”

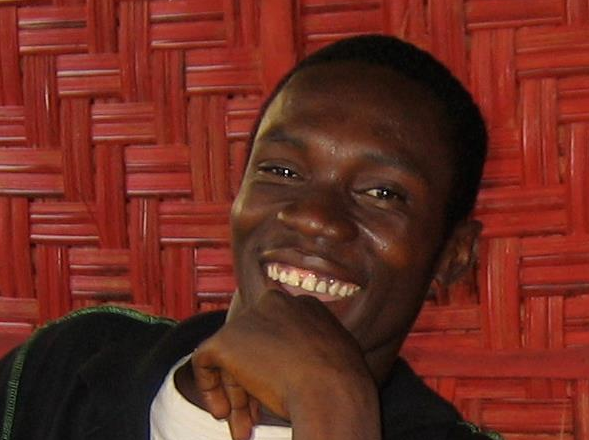

Foday was a young, rising Sierra Leonean football star. I first met him during a football game in June 2014 in Freetown. The Ebola outbreak was on the decline, yet, a ban on places of assembly, including playing sports and sport events, was still in effect. The game was held at a secluded part of a golf course because the organisers needed a concealed venue to avoid a potential fine of up to LE 500 000 (£50), a painful price to pay in the declining economy. Despite the risks, the game takes place. That is how much football is loved in the country.

The match is tense; everyone knows that there is a coach from Denmark watching and it might be the chance they are all longing for – getting a professional contract in one of the European clubs. Foday does well, so much so that within the next few weeks he is on his way to sign a contract with a Danish Superliga Club. This is a dream come true in one of the most unlikely periods. Football was not played, the clubs were not training, the national team had been banned from travelling. Watching English Premier League games in cinemas, a hugely popular activity among Sierra Leonean youth was also prohibited as part of the Ebola emergency and safety procedures. With no agents or scouts travelling to the country, he was more fortunate than he could imagine. Despite the ban being lifted within a few weeks after this game, the shut-down of Sierra Leonean football continued for another four years. For more than five years, the players lost their platform to showcase their skills but also their means of survival.

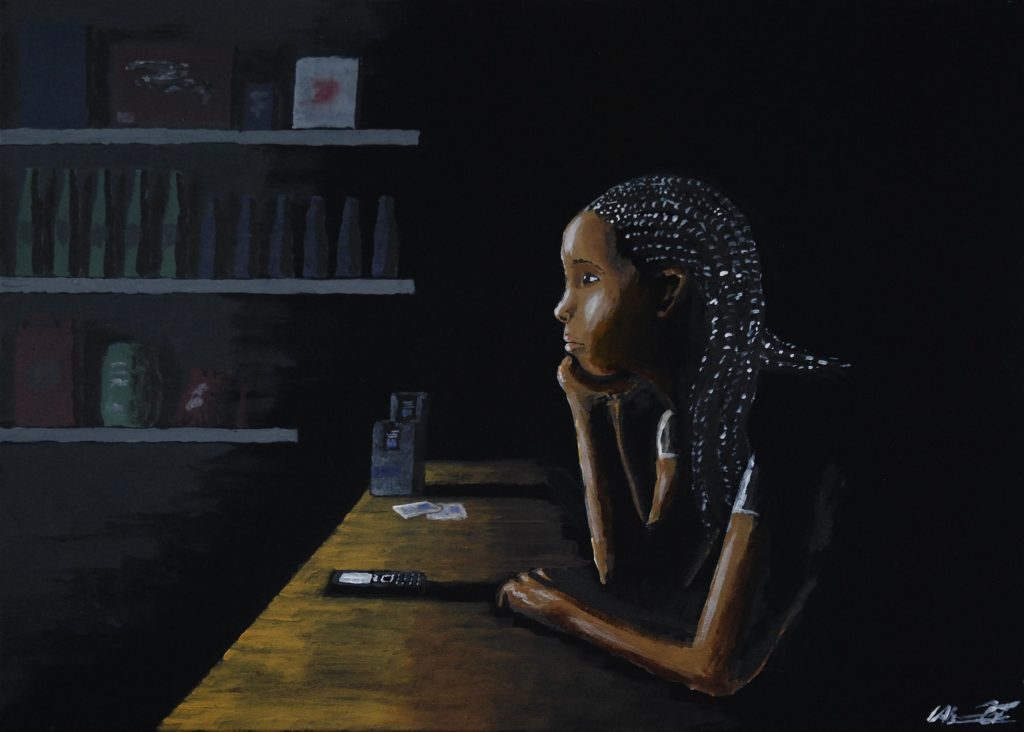

The temporary halt of the game caused many players to shift their focus and find alternative livelihoods elsewhere. “I met a friend with whom I played football, but now he was working in a store where they offload flour for bread. He told me ‘this is what I depend on presently, this is what I am doing now for a living’. It was very sad to see someone with such talent doing that stuff,” says Morris, a Premier League player. It was only earlier this year when the Premier League was resumed, but there are still thousands of the Sierra Leonean young men harbouring the dream and engaging in a committed pursuit of a career as a professional footballer.

It is a distant dream, and their chances are incredibly slim. In Europe, the odds of becoming a professional, for children playing organised football, are less than 1%. For Sierra Leonean youth, the odds are even smaller, given all the obstacles. Organised grassroots football is non-existent. The pitches are poor and equipment scarce. The majority of coaches are unqualified. Unlike in other West-African countries, where some of the big European clubs maintain scouting networks and recruit players from their academies, the possibilities in Sierra Leone are extremely limited.

Sierra Leone has never been a great footballing nation. The country has never won any major football competition, qualified for the FIFA World Cup nor produced many big football stars. The national legend, former Inter Milan striker, Mohamed Kallon, is perhaps the only Sierra Leonean footballer known by a broader international audience. And while stories like Foday’s are scarce, they do give players the hope to keep going. As John Keister, the former national team head coach puts it: “they’ve seen their colleagues gone and become professionals, that’s what is giving them the hope. You know, for example, we can be here together, going through the same processes, and then I have the break-through. Once I go, there is every belief and hope that you are going to think ‘I am going as well, I am going to make it’, so for me, I give them credit in regards to their application towards work.”

The players’ ‘application towards work’ is, indeed, admirable even praiseworthy. A Premier League player on a contract is promised a minimum salary of 500 000 LE/month (approx. £50). Some of them get more, however, as the players disclosed, most of the clubs are not keeping up with their promise and the majority get less or sometimes don’t even get paid. Yet, the players still commit and develop different strategies on how to navigate their lives as football players without a salary. As Morris tells me, “We have a musician here, called Emmerson, saying that we in Sierra Leone, we live like magicians, so I can say it’s something like that, we survive and even ourselves we don’t know how. It’s really hard here, really hard”, then he continues “The most difficult thing about being a footballer is, now you’ve made it to the Premier club, you are playing football, you wake up in the morning, go and train, and when the month is done, your parents expect something from you. It’s very, very hard. You are playing football, and you are playing at the top level, you are playing the Premier League, and you cannot support your family. Because forget about parents or kids, even just for yourself, to take care of yourself it’s very difficult.”

Struggling to make ends meet is a reality for most Sierra Leonean players. Becoming a pro footballer in a European club is not only a question of fulfilling one’s dream and passion but is also seen as the fastest way of getting rich. Still, instead of expressing their desire of becoming rich, most players talked about their hope of having a decent life and being able to provide for their family. As Devin, a retired Sierra Leonean player currently living in Sweden, reflects: “People want to come to Europe, it’s the biggest thing. It’s where everything happens; people come from Brazil, America, other places, everybody wants to come to Europe and play football because the European football is one of the biggest you can ever dream about so that’s the reason why Africans want to come out here, and also for a better life. This is where you play and sustain, you earn something, you make a living out of it. In Africa, you don’t really make that much”. However, as he adds, the reality is quite problematic; “People take advantage of that when you come out here [to Sweden], knowing that you don’t get nothing back home compared to whatever little they give out here, they take advantage of that, they say, ‘I will give him little, he will take it, he will appreciate it better than what he got home anyway.”

This, though, is only one of the unforeseen issues that Sierra Leonean footballers, who sign contracts overseas, have to deal with. Their imagined experience is highly positive. They often perceive any encounter with a European club as a guarantee for an easy and successful life. For Musa, a second division player, the image of living in Europe is pretty straightforward: “I will be happy. I imagine that everything is ok for me. I’m from zero to hero”.

Unfortunately, the expectations usually don’t meet reality. While the majority of the young men who are awaiting their chance abroad share Musa’s view, the players with the actual migration experience articulated their disillusion. Victor, a retired Sierra Leonean footballer living in Sweden, sighed as he told me: “They [the young players] have this dream that when you come to Europe, your dreams come true, no matter what. Because they do not know what happens here…”

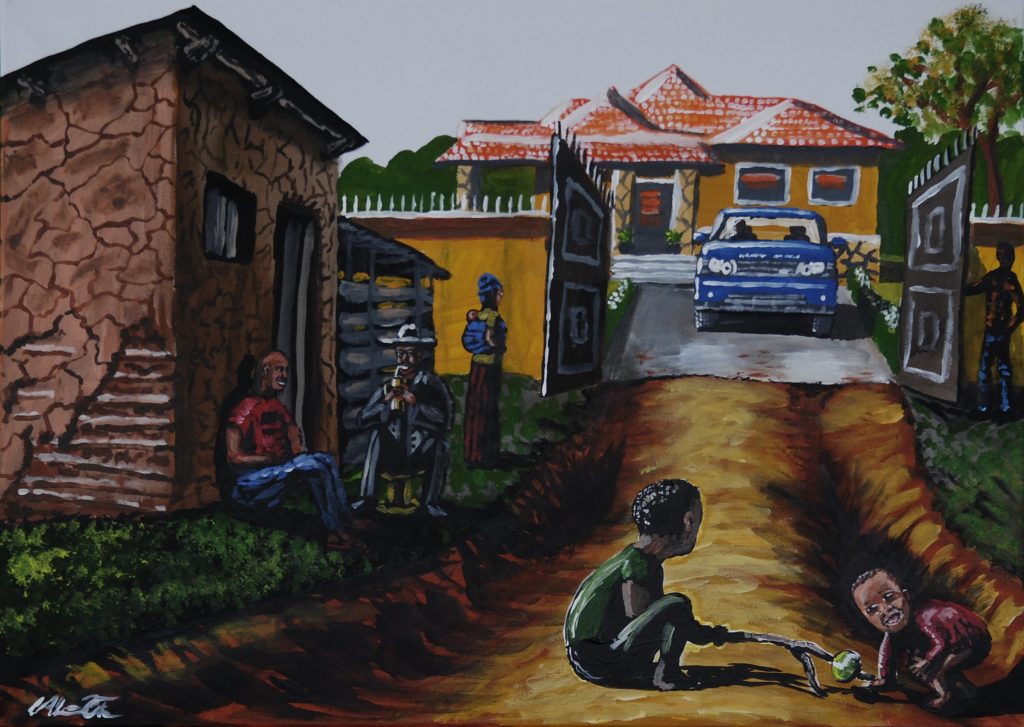

The next time I saw Foday was when he arrived in Denmark. The smile on his face showed how excited he was about the opportunity. He had made it! He signed a professional contract with a European club. We went to the club, and despite being visibly nervous, Foday tried to stay calm and look confident. Everything was different. He had turned his life around. Foday was born and raised in one of the poorer areas of Freetown. There he lived in a tin-shack home together with his family. He shared a room with two of his friends. A double mattress on the floor that makes up half of the room, a shoe rack for their boots (an essential display for any footballer) and a light bulb, no TV, no radio. Access to electricity depends on the National Power supply, which is sporadic. Today, he moved into a newly built apartment with a washing machine, dishwasher, TV, unlimited internet, and electricity 24/7.

Three months later, I revisited Foday. It was in November, the time of the year when people in Denmark enjoy drinking hot chocolate and snuggle in fluffy blankets, and when the temperature averages around 5°C. I noticed there is no duvet in Foday’s apartment.

“Where is your duvet?”

“What?”

“How do you cover yourself when you sleep”?

“I don’t. But I am fine Zora. I am really happy to be here!”

After a short search, we found a duvet and sheets in one of the storage places in the apartment. Sometimes it is the small things that make a big difference. It is these cultural differences that then affect the integration process for the players. The traffic, opening a bank account, taxes, health system, the unfamiliar products in grocery stores and simply the fact that you are surrounded by a language that you do not understand. Navigating between two considerably different cultures without any help is a tiring experience. These little struggles contribute to making succeeding more difficult for many African (international) players.

While on the pitch the players might need to adjust to a new style of coaching or different training methods, the off-pitch life is often an overlooked part of their journey. One might assume that the clubs are there to help. However, as the players themselves acknowledged, unless you are a superstar, the clubs tend not to invest in players more than is necessary. Similarly, Erik Rasmussen, a former Danish Superliga coach and owner of a second division club in Sierra Leone, explains: “You have to keep in mind that the players the club brings over are very, very cheap players. The cheaper the player is, the less effort the club is going to do to try to make them fit in. And I mean, if you buy a player for two million pounds, then you have to put a lot of effort in making him successful, but if you get the cheapest possible player, they will say, ok, why should we put this much effort into him. And these are the players from Sierra Leone, they are the cheapest players you can actually get in all instances, so the club hasn’t invested that much. Maybe they should say ‘ok, when we take a player from Sierra Leone, it will cost us £1000 or £2000 a month and then we have to put another one or two thousand pounds to make him successful’ but they don’t do that. They will say ‘ok, now we take a chance, we spend this kind of money’ but they don’t put the money into trying to make the adjustment when it’s possible for the players to get successful.”

Beyond the level of practical support, the majority of the clubs have limited knowledge of the background and culture the players come from and thus cannot offer a lot of help in cultural readjustment. Likewise, many players do not understand the specification of the new culture they find themselves in. To their disadvantage, they must both, adapt to and catch up with their teammates on the pitch and adjust and adopt a new way of life. For some, this process can take over a year. Again, the clubs perceive that as problematic. “It’s very few clubs who have the knowledge of what to do. So that means that they see a big talent, and of course, some of the best players in Sierra Leone are talented, but they haven’t built up the whole network in the club when the player arrives. I don’t think it’s racism. I think it’s more a lack of knowledge about what kind of players they start to try to work with …. I mean, any club in Europe, any clubs in the world, they just want the best players. But if it takes too long to develop that player, then most of them they give up and would rather have a player from their own culture “, Erik mentions.

The practices that the clubs implement are often questionable. For example, it is common to put players from South America, Africa and countries of the so-called ‘Global South’ to a shared apartment, often rooms, sometimes even beds. Putting six players into a small, three-bedroom apartment can help with loneliness and establishing the initial bonds; however, most players in Europe would not accept such treatment. “A lot of Sierra Leoneans wouldn’t speak out on the negative because as much as it is negative, in this whole thing they are looking at the positive part of it, you had nothing, you got an opportunity come out here and make something up for yourself, we are appreciative. Whatever it is that these people are doing to us, it’s not as bad as what we went through when we were back home. So, the good outweighs the bad in a sense. From our own perspective. But for them, I think it’s just an opportunity to get whatever they can get out of you and not give a heck about you” says Devin, the retired Sierra Leonean player.

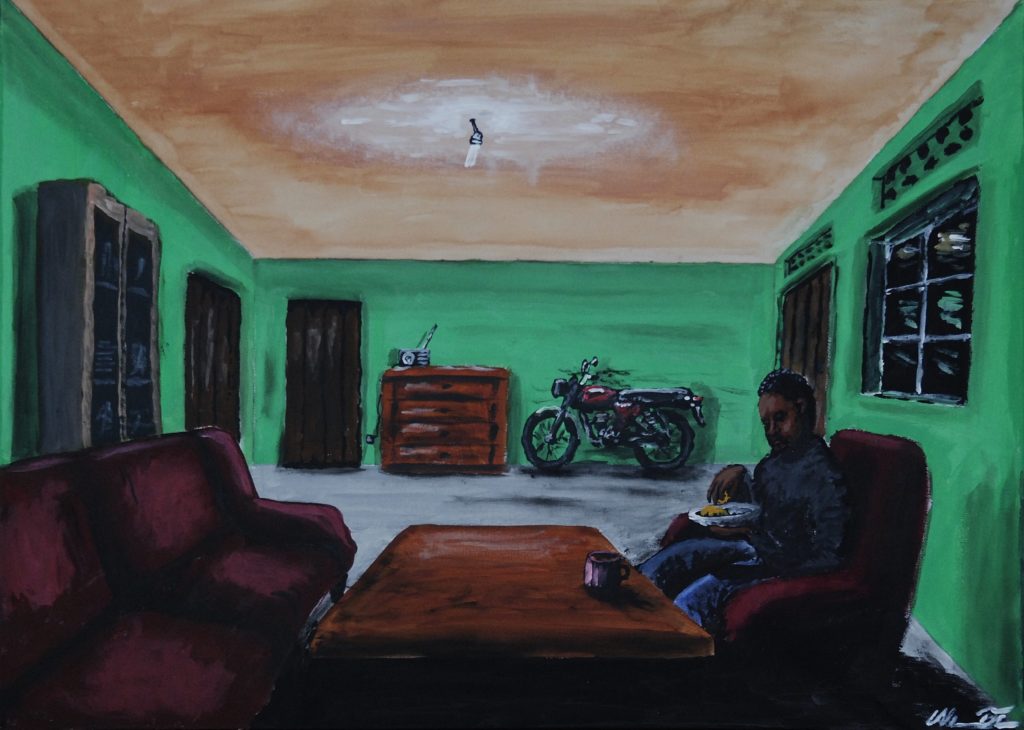

And while the practical obstacles might make life unpleasant, what the players mostly struggle with is loneliness, social isolation and racism. When we discussed the experience of settling down in Sweden, Devin reflected: “Settling down in Sweden, that was difficult. It was difficult from the start because when I came up here, I had high expectations, I was thinking different. I thought life would have been from the suffering stage to gold and diamonds and everything, but it wasn’t that… it was pretty tough. I was lonely, you know, I grew up with a different lifestyle… I am used to being outside, run under the sun. I am living here, the place is cold, I am freezing, and literally have nobody to talk to. I live in my apartment by myself, and I was pretty young when I came here so the fact that I was in my own place, in my own space, it was great, it was big but then at the end of the day I realised that there was so many things that I miss.”

Whilst the Scandinavian countries rank at the top of indices for ‘happiness’ and wealth, they also outrank other countries and score the highest among countries where it is difficult to create friendship for foreigners, but also in the average number of people in a household. For Sierra Leoneans, who are known for their friendliness, and co-living with family, friends or extended family is part of the culture, might be the private, closed life in Scandinavia quite isolating. As Devin adds: “You can live in a house and your next-door neighbour doesn’t really know you, for years you see each other and you probably say “hi” and that’s it. In this country it is difficult to make new friends, people always keep their old friends”. His sentiment was shared among many Sierra Leonean migrant players that I talked to. By moving countries, and in this case continents, one loses the proximal social and support networks. The players stay connected to their close ones through social media and WhatsApp. Still, besides teammates and staff from their football clubs, they all pointed out that they mostly do not know any people outside their clubs. Yet, they perceive it as an advantage to help them to stay focused on their career as they have a lot at stake.

The pressure on the players is enormous, apart from being able to fulfil one’s ambitions they generally cannot keep people back home of their mind. And while living abroad is not easy, coming home might bring a serious dilemma as well, particularly for players from a more disadvantaged background. “No matter what kind of situation you find yourself into here, it is difficult to go back home because people back home have a 100% expectation from you. And if you come here and you don’t achieve that goal, your dream, you will always think ‘when I go home, my people have this kind of expectation and if I don’t achieve it or if I don’t have it, I don’t see the reason to go there’. So that makes it so difficult for players to forget about everything and get back home”, Victor explains.

This is also how Foday’s story ends. After a year in Denmark, his contract was not extended, and he was about to go back home. However, he never made it to the flight. Rumour has it that he joined his brother in France, met a partner, had a child and is currently an asylum seeker. Presently, with his football career abandoned, he is an undocumented migrant who cannot sign a contract with any club. Sometimes, the high expectations of friends and family makes going home not an option.

The situation is a vicious circle to which the migrant players themselves also contribute. As Victor admits: “It’s difficult, because we, who are going for holidays [in Sierra Leone], we are putting 100% pressure on them. Because when we go, we drive big cars, eat big food, go to hotels, night clubs, spending money all over, so they get that excitement, they get that thought ‘oh, Europe is heaven’. The people who go back home for holidays, they show the kind of picture that everything is WOW here in Sweden or Europe. No matter which kind of situation they find themselves in here, when they go back home, they show this kind of picture that they are living a luxurious life so the boys back home, they are so eager, they are so excited to be in this situation too.”, and explanation does not help, “There is nothing that you can tell them that they would trust. They will tell you ‘You say it’s so difficult there, but you are there, why do you never think to come back if it’s so difficult?!”

The question is then given these challenges, what are the possible solutions? What would be the best advice to get players prepared for their life abroad, and make the clubs more considerate? Devin concludes: “Well, leave your expectations behind. Don’t come here thinking your life is gonna be all brilliant because it’s not even about money, it’s just the social activities you got back home you won’t have here. It is a whole different lifestyle you are getting yourself into. You are going into this deep hole and you don’t even know what’s at the end of the tunnel. So, don’t come here thinking ‘oh, my life is going to be better now, everything is going to be alright’. No, in the same way how you have been struggling, you come here and struggle, just in a different format.”. . . . “And if the clubs sign a player, they should start valuing these players like they value the Swedish players as well, give them what they deserve instead of just going ‘He just came from Africa, he was earning nothing when he played football, let’s just give him this amount, he’s going to take it’. Give the value to the player that he deserves, the money he deserves, the life he deserves, give it to him. I think if the Swedish people stop looking at us as Africans and look at us as footballer players, they will help a lot more.”

Zora Šašková is a PhD researcher at the School of Sport, Ulster University. Her ethnographic research examines the ways in which various socio-economic and cultural issues that are specific to Sierra Leone influence the decisions of young men to actively pursue a career in professional football abroad. She also explores their experiences and expectations as Sierra Leonean football players and analyses their imagined and actual migrant experiences. Additionally, the study investigates the dynamics of the development of the emerging football migration network between Sierra Leone and the Scandinavian countries.

It’s raining in Freetown and the traffic is, as usual, slow on the road through Congo Town towards Kroo Town Road. The radio announcer is going through the obituaries in a solemn, deliberate monotone, the names different, the pattern the same: Mr John Koroma of Kissy Town passed away on said date leaving said relatives in said location… repeat… repeat… repeat. Variations on the theme. After a few minutes of death reports the obituaries are rounded off with a few snatches of Abide With Me, by which time we have actually reached Kroo Town Road. We swing right on the now tarmacked road that runs parallel to Adelaide Street and pass what, ten years ago, was the Pentagon car wash, a hangout for ex-combatants and others struggling to make a living in a world of ‘no war no peace’ under conditions that one of them described as ‘exorbitant poverty’.

It’s raining in Freetown and the traffic is, as usual, slow on the road through Congo Town towards Kroo Town Road. The radio announcer is going through the obituaries in a solemn, deliberate monotone, the names different, the pattern the same: Mr John Koroma of Kissy Town passed away on said date leaving said relatives in said location… repeat… repeat… repeat. Variations on the theme. After a few minutes of death reports the obituaries are rounded off with a few snatches of Abide With Me, by which time we have actually reached Kroo Town Road. We swing right on the now tarmacked road that runs parallel to Adelaide Street and pass what, ten years ago, was the Pentagon car wash, a hangout for ex-combatants and others struggling to make a living in a world of ‘no war no peace’ under conditions that one of them described as ‘exorbitant poverty’.