It’s raining in Freetown and the traffic is, as usual, slow on the road through Congo Town towards Kroo Town Road. The radio announcer is going through the obituaries in a solemn, deliberate monotone, the names different, the pattern the same: Mr John Koroma of Kissy Town passed away on said date leaving said relatives in said location… repeat… repeat… repeat. Variations on the theme. After a few minutes of death reports the obituaries are rounded off with a few snatches of Abide With Me, by which time we have actually reached Kroo Town Road. We swing right on the now tarmacked road that runs parallel to Adelaide Street and pass what, ten years ago, was the Pentagon car wash, a hangout for ex-combatants and others struggling to make a living in a world of ‘no war no peace’ under conditions that one of them described as ‘exorbitant poverty’.

It’s raining in Freetown and the traffic is, as usual, slow on the road through Congo Town towards Kroo Town Road. The radio announcer is going through the obituaries in a solemn, deliberate monotone, the names different, the pattern the same: Mr John Koroma of Kissy Town passed away on said date leaving said relatives in said location… repeat… repeat… repeat. Variations on the theme. After a few minutes of death reports the obituaries are rounded off with a few snatches of Abide With Me, by which time we have actually reached Kroo Town Road. We swing right on the now tarmacked road that runs parallel to Adelaide Street and pass what, ten years ago, was the Pentagon car wash, a hangout for ex-combatants and others struggling to make a living in a world of ‘no war no peace’ under conditions that one of them described as ‘exorbitant poverty’.

I’m heading for the office of Prison Watch (a local human rights NGO) on Gabriel Street at the other end of the road but it was Pentagon that was my first point of reference in Sierra Leone. It was there my encounters with marginal, hustling youth began (thanks to Mats Utas!). And it was not far from there that I first encountered Flavour.

With extra irony a funeral car cut in front of us as I listened to the somber voice of the obituary announcer. My eyes and my thoughts drift left in the direction of the King Tom cemetery where I once attended the Muslim burial of a little girl, the daughter of one of the guys I had gotten to know in Camp Diva, down Kroo Bay. She died. She’d been cursed, I was told. Flavour was there that day too.

My thoughts are filled with dying. Six months ago, when I was here last, death was made conscious in a different fashion. The shroud of Ebola still hung close, a dominant part of the visual landscape. Advertising hoardings, posters, bumper stickers all urged caution. A-B-C: Avoid Body Contact was the advice. The risk of the spread of death had gone viral. Today, the posters are faded, the hand-washing points are unsupervised and under-used. No longer are you obliged to wash your hands and have your temperature recorded before passing through passport control at the airport (though you are still controlled on departure). No longer are taxis only carrying four passengers to inhibit body contact. Life seems to be going back to pre-Ebola normal. Which means normal dying too.

Flavour was not supposed to die. Meaning I did not expect him to die. At least not yet. I’m shocked to hear it. Reported to me cursorily. I’d just hung up on a phone call with Salim, just touching base and greeting his five-year old son (my namesake), when he called me again: ‘Mr. Andrew, I forgot to tell you, Flavour is dead’. To the point. I’m stunned.

Flavour and Salim were two of my closest connections in Kroo Bay during fieldwork conducted in 2006. From the funeral service sheet I can see that Flavour must have been 26 years old when I met him. I probably knew that but at the time it was of little consequence. He was living in Kroo Bay on land reclaimed from the sea in a panbody. I spent a night there once, just to see what it was like – my little luxury. His girlfriend, at the time, was obliged to give up her mattress to accommodate me. Meanwhile, Flavour and Salim slept in my jeep parked up on the road ‘for security reasons’, they said. The three of us were often together in the camp or moving through the city. A couple of times I was taken to dubious clubs where we drank star beer and danced awkwardly. On one of these late night escapades I recall Flavour pointing at the former headquarters of the Criminal Investigation Department, as we passed by and alluding obliquely, possibly autobiographically, to sordid torture conducted behind the walls sometime in the not too distant past.

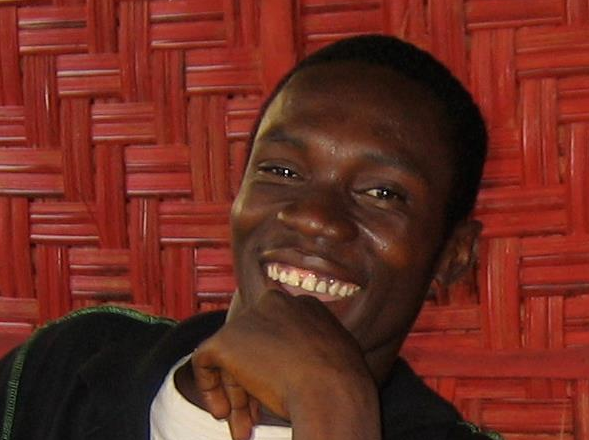

When I first met Flavour his hair was dyed and he was easily recognizable. His father was a tailor. He had no intention of following in those footsteps. He drank more energy drink than beer but was often semi-stoned. Neither he nor Salim were ever especially talkative. Over the weeks and months that we got to know each other we were often simply sitting quietly together gazing at the sea or patrolling the city as I sought to get a grasp of what it was like to live a life under circumstances compromised by poverty and lack of opportunity. During the following decade, I would usually hook up with them every time I was in Sierra Leone. I saw Salim more often than I saw Flavour.

Flavour was not supposed to die. But he came close before, probably more often than I know. On one occasion he was involved in a fight and was stabbed in the chest, not far from his heart. Once again it was Salim who informed me, desperate to get hold of some cash to facilitate treatment. Slowly the stab wound healed but for months afterwards he was short of breath and would experience pain. One late night out, I was deeply troubled by his aggressive attempts to defend me after I got into an argument with a clumsy driver. He was simply not in a fit physical state to escalate a conflict. He was not fit to fight.

Palavers are common in the life of a young hustler in Sierra Leone’s poor urban neighbourhoods. And Flavour was no stranger to conflict. I suspect he was wilder in his younger days before I met him than he was subsequently. Indeed, my first introduction to him was because he had spent time in the Central Prison. There would be other nights spent there too and in the police cells. But my sense was that time had mellowed him. The last time I saw Flavour he told me his girlfriend had given birth to a baby girl, named Marie after my own daughter. He had a child, indeed now two children, the second born just two weeks before his death. He had become a man.

Were I to search my field notes from 2006 I am certain Flavour’s name would be everywhere. It is obviously not his given name but until I had to send him some money when he was sick, I did not even know his real name. He was always simply Flavour. The burial service sheet features his given name – Doe Smith – but, appropriately enough, with the suffix ‘aka Flavour’.

Flavour was not supposed to die.

Andrew Jefferson is a psychologist working as Prisons Researcher at DIGNITY – Danish Institute Against Torture