After six days of patiently waiting, during which 25% increments of Sierra Leone’s 7 March presidential vote were gradually released, on the evening of 13 March, chair of Sierra Leone’s National Electoral Commission (NEC) Mohamed Conteh announced final results and in doing so confirmed a runoff would be needed to decide who will become the country’s next leader.

The first-round result gives a slender advantage to the Sierra Leone People’s Party (SLPP) and its presidential aspirant Julius Maada Bio (43.3%) who will face off against Samura Kamara, the candidate of the incumbent All People’s Congress (APC), who trailed Maada Bio by just 0.6%. 14 other candidates shared the remaining 14% of the votes and these ballots will be up for grabs when the two leading candidates contest again on 27 March.

Choosing sides

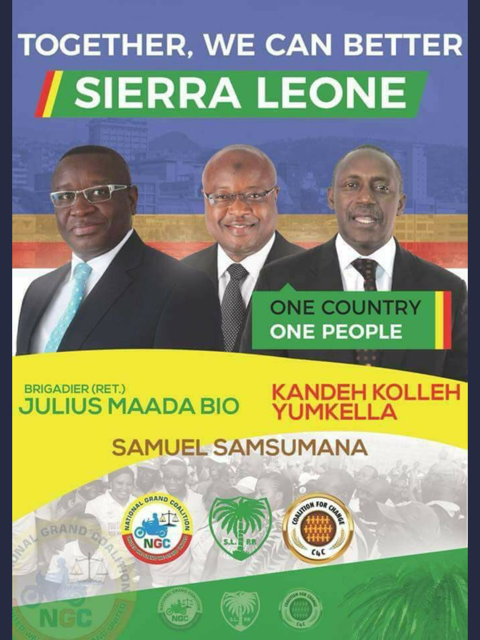

Particular attention has already turned to the aspirants who placed third and fourth in this election – Kandeh Yumkella and Sam Sumana – and who they might throw their weight behind in the second round. Social media is already awash with unofficial posters – created by party supporters – that depict the possible political realignment. But both have complicated recent histories with the leading parties, with Yumkella having left the SLPP to form the National Grand Coalition (NGC) in late 2017 and Sam Sumana being sacked from his role of vice-president and thrown out of the APC in 2015 in circumstances that were constitutionally contested.

Unoffiicial poster tweeted by @vickieremoe

Unoffiicial poster tweeted by @vickieremoe

Already the APC, through outgoing vice-president Victor Foh, and the SLPP have sought to approach Sumana knowing that his loyal supporters in Kono – the only district other than Kambia in Sierra Leone where neither the SLPP or APC won the majority of votes in the first round – are likely to follow his lead. Sumana won 3.5% of the presidential vote, and his Coalition for Change (C4C) party is expected to win over two-thirds of the parliamentary seats in the district. Both parties will, no doubt, be thinking about what they can offer behind the scenes to secure his support. It would likely have to be something substantive given that Sumana served as vice-president for eight years and sought $210 million in the lawsuit he filed at the ECOWAS Court contesting his dismissal. A return to that position looks unlikely but a pardon for his dismissal and a return of his perks or a Ministerial position are possible. Given his Kono support base, the Ministry for Mines might be appealing.

Yumkella and his NGC are more difficult to predict. His stated message of change, and of delivering a ‘third way’ for politics in Sierra Leone ultimately failed to translate into widespread popular support, with his party winning just 6.9% of the vote. Many of those votes were taken in northern districts, territory normally a stronghold of the APC, where Yumkella himself holds personal ties. It remains unclear who those voters might offer their support to in the next round.

Yumkella – who successfully contested for a parliamentary seat in his home district of Kambia – has consistently sought to distance himself from either party during the campaign and could choose not to support either in the runoff; by encouraging his voters to choose as they wish or not to vote at all. It also is not clear whether, if Yumkella was to throw his support behind the SLPP, that his supporters would uniformly do the same. Although the message of change has been a key component of both campaigns, regional considerations and accompanying ethnic identities continue to play a significant role in national voting patterns.

Nonetheless both parties are likely to privately court Yumkella given the fact that he holds the third largest percentage share of the vote. His break from the SLPP centred on his desire to be the flagbearer; he might therefore expect something close to the vice-presidency or a promise to stand him as a presidential candidate in 2023. The APC, in addition to potentially offering a ministerial portfolio could also use an adjourned court-case – which they pursued throughout the campaign to challenge the validity of Yumkella’s candidacy for holding dual nationality – as a negotiating tool: by offering to drop the case if they were to win, given that the case could still, in theory, be used to bar Yumkella from taking up his parliamentary seat.

The perils of becoming king

However both potential kingmakers are well aware of the recent history of aligning with one of the leading parties in a run-off. In 2007, Charles Margai, having split from the SLPP to form the People’s Movement for Democratic Change (PMDC), won 13.9% in the first round and became a kingmaker in the APCs run off victory. By 2012 however, the 10 parliamentary seats his party had been won were lost and his percentage of the presidential vote dropped to 1.3%. In 2018 Margai came 8th with 9,468 votes or 0.39%.

But even candidates like Margai, those placed fifth to sixteenth, will have some part to play in the run-off. Each can choose to exchange their votes – even if they are only a few thousand – in return for something; an ambassadorial position or a influential district level role perhaps. Offers and counter offers are likely to be a key part of the political conversation in the next two weeks. Here the importance of SLPP’s first round victory may reveal itself. Having trailed in every poll since winning the 2002 election – it came second in 2007 first round and lost the run-off and lost in the first round in 2012 – it has shown, to both voters and potential political allies, that it can win at the polls in 2018. Its supporters also insist that the first round results show that 57% of the country is dissatisfied with the APC’s performance; a different interpretation would suggest that some APC supporters expressed their preference for a smaller party but are likely to “come home” in the runoff. This “back to root” narrative has already been popularised by APC supporters.

With less resources at its disposal than the APC, the SLPP’s first round slender advantage might prove to be important. So too will ensuring that existing supporters turn out to vote. In 2007 turnout for the runoff was 66%; down from 76% during the first round. But making sure that not too many people turn out will also be a factor. Citing over-voting, results from 221 polling stations (the details of which have still to be released and may offer some important insights ahead of the second round) were annulled by NEC in its 13 March declaration of results.

More equitable development, less political division?

The presidential run-off promises to be the closest post-war electoral contest. Whoever wins will not only have the huge task of resurrecting the economy, tackling corruption and improving the delivery of basic social services. They will also need to “seriously address the question of national unity”, says OSIWA Country Director Joe Pemagbi. One concerning aspect of this election is that despite a sense the campaign was more issue-based, and the presidential candidates had to defend their platforms during a national televised debate, the voting patterns revealed by the election results show a country clearly divided along geographic, and to some extent, ethnic lines. The SLPP averaged 8.9% in the four northern districts of Bombali, Tonkolili, Port Loko and Karene; whilst the APC took 9.9% in the four south-eastern districts of Bo, Pujehun, Kailahun and Kenema.

In some ways, instead of offering a third way NGC and C4C simply slotted into these old regional politics. They were key in pushing the vote to a runoff and now find themselves in a new position but they did not change the political game at all; but rather benefited from its existing features. In some ways they even contributed to the further entrenching of ethno-regional/autochthony politics. In Kambia, whilst Yumkella may not have campaigned explicitly on those terms, the debate between APC supporters and those who were contemplating whether to jump ship to NGC focused on the importance of electing a “son of the soil”. This was heightened after the failure of Alimamy Petito Koroma, former Ambassador to China from Mabolo chiefdom in Kambia, to win the APC leadership contest. Tellingly, debates around the emergence of the NGC in Kambia revolved around questions of whether Yumkella was “enough” of a son of the soil capable of bringing development to his home district. A significant focus of discussion for example centred on his failure to rebuild his village, in Samu, effectively.

The APC’s politics of regionalism and in particular the development of President Koroma’s hometown of Makeni has increasingly meant that voting for a son of the soil is seen as a vote for development in the district. For many, voting ethno-regionally is a product of calculations that improved development and increased access to jobs tend to result from electing “one of our own”. This is based on evidence of development strategies in recent years rather than some sort of primordial voting behaviour.

For those looking for green shoots of optimism the make-up of parliament is a potential positive. Results are not yet confirmed but it seems that at least four parties will be present, a break from the SLPP-APC duopoly on the last parliament, which was routinely dismissed as nothing but an executive rubber stamp. The possibility of a president from one of the two main parties and an legislature controlled by the other is not too far-fetched. This scenario might led to more consensus-based politics and, crucially, more equitable nationwide development.

Luisa Enria is a Lecturer in International Development at the University of Bath. Follow her on twitter at @luisaenria.

Jamie Hitchen is a freelance researcher and writer and co-director of AREA Consulting. Follow him on twitter at @jchitchen.