Sierra Leone has a new president. And despite being challenged prior to the elections, the two party-system dominated once again. After two five-year terms under Ernest Bai Koroma of All Peoples Congress (APC), the second giant, the Sierra Leone Peoples Party (SLPP), takes over again. Julius Maada Wonie Bio of SLPP defeated APC’s Samura Kamara by gaining 51.8% of the vote in the runoff on March 31, 2018.

Sierra Leone has a new president. And despite being challenged prior to the elections, the two party-system dominated once again. After two five-year terms under Ernest Bai Koroma of All Peoples Congress (APC), the second giant, the Sierra Leone Peoples Party (SLPP), takes over again. Julius Maada Wonie Bio of SLPP defeated APC’s Samura Kamara by gaining 51.8% of the vote in the runoff on March 31, 2018.

As the 5th president of Sierra Leone, Bio has been sworn in as president on April 4, 2018. He is a familiar and controversial face in local political landscapes. Now a retired Brigadier, he briefly held the position as military head of state after leading a coup in January 1996. Bio justifies this manoeuvre as enabling the end of the civil war and the country’s return to democracy. His followers appreciate him as the man who, during the civil war, started formal negotiations with the Revolutionary United Front (RUF Rebels), conducted national elections and handed over power to Ahmad Tejan Kabbah after Kabbah won the elections. Critics point towards his use of force to dictate the political arena. Bio was also the SLPP presidential candidate in the 2012 presidential election, then losing to Ernest Bai Koroma. Yet, while he is well-known, his next moves remain elusive. The onset of a new political chapter raises numerous questions, nourishes hopes and feeds anxieties about the future of post-conflict and post-pandemic Sierra Leone.

What might change and what might stay the same? This is perhaps the question in many people’s minds though probably most are thinking about local livelihood possibilities, education opportunities for their children, or whether the power supply will improve. Few will be thinking about prisons.

As prison and confinement researchers we are specifically curious about the consequences for the criminal justice system, for models of punishment and for practices of confinement in Sierra Leone. Will Bio reshuffle, hold constant or reconstruct? Will he scrutinise existing mechanisms and structures, nourish what worked and aim to change what has not? Will he continue down the same path as his predecessor? Might there be stagnation, or may there be radical change?

Our questions amalgamate in one big issue, resources, and fork into two areas, personnel and funds. Based on our personal experiences, we reflect on the possible effects of a reshuffling of funds and personnel.

During Luisa’s fieldwork and while negotiating access to police stations, courts and Pademba Road prison, a single mantra was recurrent. While members of the judiciary and law enforcement officials were adamant that they are politically neutral, they were still employed under a specific administration. Hence the message while voiced in manifold different ways, scenarios and by different people sounded something like

“I will always grant you access. You can be in my court, prison, police station whenever you want, that is if APC stays in power because if not, who knows where I will be.”

And in effect, who knows? A change of ruling party in Sierra Leone has typically meant a change of faces at senior levels in the Judiciary and the Correctional Services. However, the current situation is unique because the former ruling party still have a majority in parliament. Hence one must wonder: is this reshuffling inevitable? How fast might it happen? And what will it mean for the work under way to push the justice sector towards rights-compliance? And more broadly, does the fact that presidential power has in fact changed hands imply a consolidation of democracy?

In Sierra Leone—a country based firmly on informal social and group ties—self-interest and possibilities for action are in a dynamic relationship with the interests of others, as they are enhanced and limited by prospects which arise from interactions. The impact and effectiveness of non-governmental agencies, interest groups, international- and state organisations is ‘domesticated’ in that it rises and falls with the strength of one’s social networks. It is this related- and connectedness which characterizes people’s actions and directs the way they structure their private and professional lives.

Like any other job, the presidency does not only come with a set of laws, regulations and official tasks, but with a gigantic appendage of social structures, relations and practical norms. In a country heavily influenced by and dependent on foreign actors and agencies the balancing of different interests and the nourishing of relationships is highly delicate. However, the navigation of systems that have been created between the former government and the landscape of people it engaged with, cannot be comprehensively handed over from one political party to another, much like a new partner is unable to continue the relationship of a former without adjustments and recalibration. There is no roadmap for these relationships. Hence, each string of this complex web will need to be renegotiated and reconfigured as the informal terrains of sociality are remapped. Consequently, we must wonder what will happen to the network as such and to all its different aspects? Will it collapse? Will a new network form? Will it continue unhindered? Will it be scrutinised?

Since 2006 when Andrew began fieldwork-based research on prison practice in Sierra Leone there have been a few changes in the upper echelons of Correctional Services. Director General Showers was appointed in 2008 and given his openness to reform-oriented national and international programmes optimism was relatively high. In 2010, he was replaced by DG Bilo under rather dubious circumstances following a prison ‘walk out’ which an official inquiry found him not culpable for. DG Bilo has been in charge during the period when the Correctional Services Act (2014) was passed which cosmetically updated the former Act, for example by changing the names of prisons to correctional centres and officers-in-charge to prison managers, in lieu of addressing some of the more fundamental issues of penal practice. More recently, bail and sentencing guidelines have been adopted and Saturday courts initiated to deal with the backlog of court cases in the post-Ebola landscape partially responsible for the over-populated prisons.

Our sense is the Correctional Services under DG Bilo have become slowly more open to outsiders, keen to scrutinize prisons either from a research perspective or from a perspective informed by the desire to promote human rights and prevent torture and degrading treatment. Senior staff have partaken in exchanges (dialogue and visits) with reformers and scholars and with prison services from other parts of Africa facing similar challenges. The prison rules, that is the rules that govern the everyday practice of frontline staff, are under review to make them compliant with the UN’s Mandela Rules (which indicate minimum standards for prisons). Under the auspices of a UNDP supported programme, managed directly by SLCS, not only are these rules being reviewed but human rights audits have been conducted in selected prisons around the country. Hence, there have been encouraging signs, but there is a long way to go and the question about what will happen under the new political constellation is thus pertinent.

Our second major point regards the question of what the new presidency might mean for the criminal justice system, especially for prisons and legal reforms and their implementation. During Koroma’s time, Sierra Leone has ratified numerous new guides, regulations, laws, protocols, reviews and additions. Yet, the trend has seemed to be to create another review board, addition or organisation tasked with making things better on paper rather than taking on the immense task of solid implementation. The web of forms, protocols, reviews and regulations notwithstanding, access to affordable and quality justice remains limited and police stations and courts are faced with case-loads which far exceed their resources; the former being unable to conduct proper investigations and the latter in-depth analysis of cases. De-criminalisation of petty crimes has been talked about but so far has not taken place, and, taken together with a complex bail system, prisoners remain on remand for prolonged periods of time. The overpopulation of prisons has worsened, and conditions remain dire with frontline authority still inappropriately shared between certain prisoners and guards. Most problems boil down to a lack of financial and human resources and a disconnect between what is ratified on paper and what happens in practice. One judge shared with Luisa; “We are good at making laws, but less good at making laws work. So, we just make a new law instead of implementing the old one because it is easier to imagine how perfection looks like in your head than when looking at the mess on the ground.” Along similar lines, in response to a query about the possibilities of post-prison aftercare, a senior prison official shared with Andrew something like ‘it’s in our books but not in our practice.’ The implementation gap is massive.

Regarding criminal justice, the recurrent mantra was this:

“We have no money for lawyers and judges. Now I am handling about 30 cases a day from Monday to sometimes Saturday. I don’t have time for them. I decide, adjourn and dismiss quickly.”

“Well, the new bail conditions should reduce the number of remand prisoners, but at this time and before the elections, we cannot say what will actually happen.”

“As a police officer I can tell you the resources are lacking for us to conduct proper investigation. It is a bit of a game here with the justice.”

“The laws we have now are too rigid and people end up in prison who should not be there. And already the place is too overcrowded. Maybe sometime after the elections, we will see if they review them.”

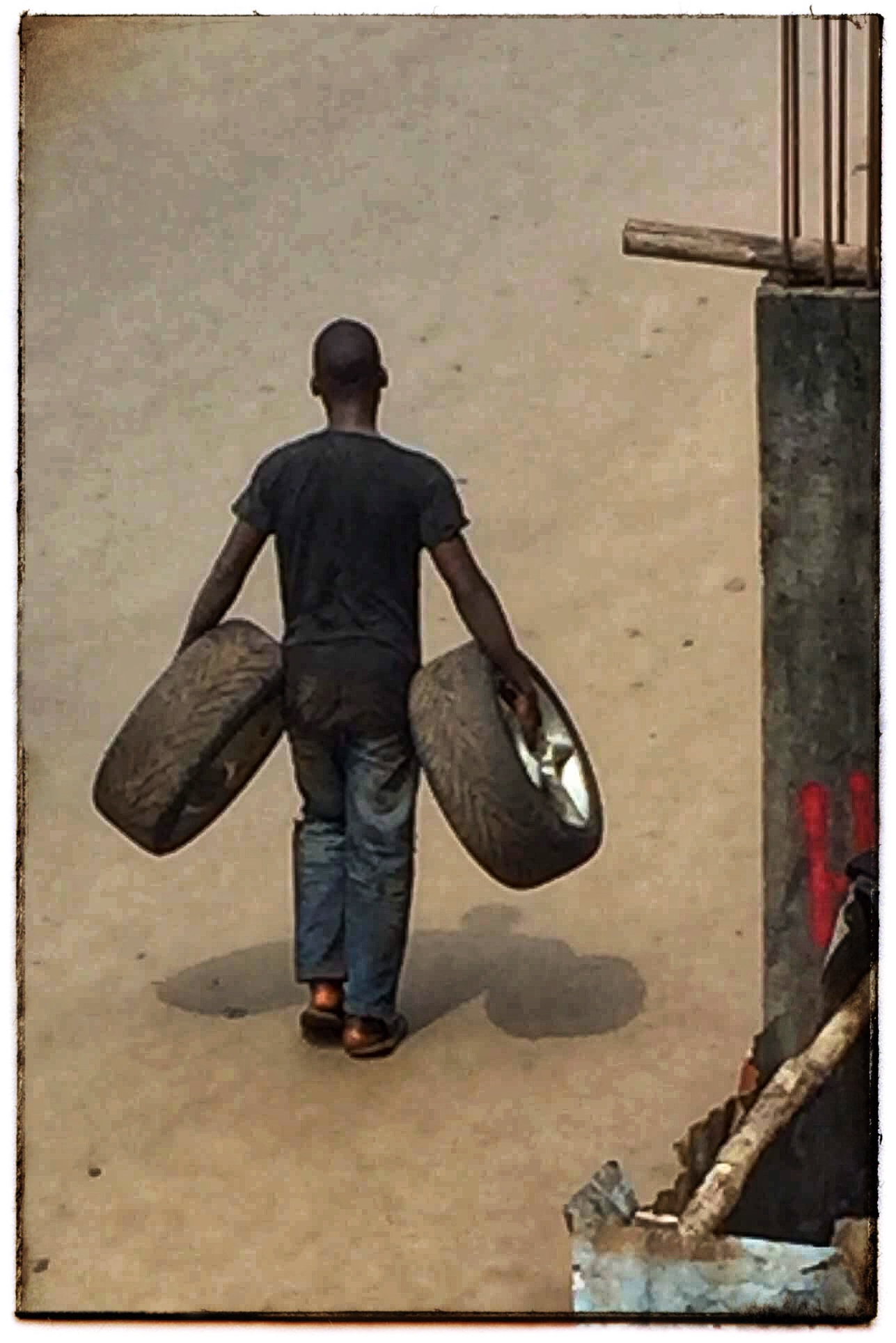

Some of the laws passed in recent years, have furthermore had adverse effects. To give just one example, the Sexual Offences Act which—to prevent the rape of young girls by older men—has raised the age of consent to 18. However, often, it is marginalised youth who end up in prison for sleeping with underage girlfriends. Rather than preventing rape, the law has criminalised some young people’s sexual relationships leading to a forced separation of young couples and to young men and boys facing prison sentences of up to 15 years. Will these laws and their consequences be scrutinised?

Our third question regards the allocation of funds. Prisons are rarely at the top of the political agenda. Resources are rarely channeled in their direction despite evidence of appalling, degrading and inhumane conditions for prisoners and the laments of front-line staff that their own conditions of work are not much better. The Ebola pandemic posed further challenges to an already dire situation. An employee of AdvocAid a paralegal organisation that advocates for the rights of women in prisons stated:

“You see after Ebola all the funding was re-directed towards the health sector. Nothing remains for the criminal justice sector now. We will have to wait for after the elections to see what will happen.”

How will the SLPP address the shift of development funds towards the health sector which resulted from the Ebola pandemic? Will a balancing of funds take place? Previously, and adding to the focus on the health sector, the resources reserved for the criminal justice system have been concentrated. After the Sierra Leone Legal Aid Board (LAB) was formed in 2012 with the responsibility to provide free legal aid services for the poor including legal representation, advise, assistance, legal and community-based outreach, alternative dispute resolution etc., most government funds were given to the LAB which was in turn asked to distribute funds to respective organisations. But due to the LAB’s struggle to make ends meet, this re-channelling has not taken place. With corrections and rehabilitation receiving the lowest amount of funds as compared to the courts and law enforcement to begin with, organisations working in and on prisons are struggling. It remains unclear whether a reallocation of resources to those organisations extending support to people involved with the criminal justice system will take place. Prisons matter though. Those who get caught up in the system do eventually come out – are they better citizens or worse citizens as a result? Prisons are public institutions and matter, not simply because of the plight of their occupants but because they are a particular sharp and intense representation of the relationship between state and subject.

In 2006 Andrew got to know a group of newly released ex-prisoners and followed what scholars sometimes call their ‘re-entry’ into society. For many of them it was a ´time of deep uncertainty. Having been arrested six years earlier while the country was still at war they came out of prison under conditions of fragile peace and fragile futures. For some the elections of 2007 created opportunities as they were drafted into the personal security detail of the new president and given quite significant positions. How will they fare in the new dispensation? And how will the many others for whom prison typically increases the heat of pre-existent deprivation?

Madame Kadiatu Conteh, one of Luisa’s closet friends, once said:

“Imagine the rainy season. One night the rain comes heavy and suddenly rain starts pouring into your house at hundreds of different points. Immediately, you can only close one hole. Which do you choose? Maybe the one over your child, or the one which rains on the rice or the one which rains on your medicine. But then later, you have to come up with a system to fill all the holes even though you have far too little people and tools and money to do that and that requires some mad creative skills.”

The new President faces no small task. Will he be satisfied just patching or will he target root causes and aim for comprehensive solutions? What is clearly necessary, from our point of view, is a concerted effort to move from paper to practice, from ‘imaginary reform’ to meaningful change. Paradoxically perhaps, bridging this gap will require new leaps of imagination, reinvigorated dreams and greater joined-up thinking by politicians, activists and academics alike. Imagine the rainy season; dream of the sun.

Luisa Schneider is a DPhil candidate in Anthropology at Oxford University and a visiting Fellow at the University of Copenhagen and at DIGNITY. Follow Luisa on academia.edu at https://oxford.academia.edu/LuisaSchneider

Andrew M. Jefferson is a senior researcher at DIGNITY – Danish Institute against Torture and cofounder of the Global Prisons Research Network: www.gprnetwork.org Follow Andrew @andymjefferson