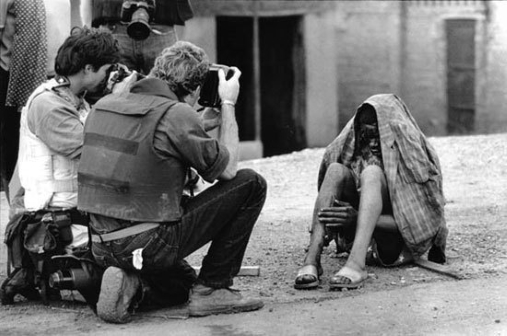

The recent Ebola crisis in Sierra Leone, Liberia and Guinea has spurred a range of responses from all over the world. Some of these responses exemplify the ongoing stereotyping of Africa and Africans. Public discourse, unfortunately, still has the tendency of addressing Africa as a country, a war ridden space full of sadness and its inhabitants as savage and helpless. But stereotypes are not limited to these images of misery.

Other stereotypes romanticize Africa and Africans, they convey an image of the exotic and unspoiled continent. Moreover, various perspectives convey an image of poor people as a noble poor. These images may be highlighted in the context of Ebola, but they are always present. They are part of many people`s understanding of Africa, part of ignorant perspectives on the continent and the people.

Africa is a country

Of course we all know that Africa is not a country, yet the idea of Africa as a country is continuously reinforced in a variety of public platforms. For example, as a response to the Ebola crisis, a variety of countries implemented strict visa regulations for people coming from all over Africa. Whereas I understand that health controls are intensified when it concerns people (black and white) coming from the three Ebola hit countries, it is shameful that travelling becomes harder and harder even for people coming from other African countries. In Norway, people in a plane with a Kenyan with fever on board were not allowed to disembark due to fear of Ebola. Yet, Kenya is quite far from the three Ebola hit countries. The HvA, a tertiary educational institute in Amsterdam, The Netherlands, has prohibited its students from travelling to the continent for internships or study. One would expect differently from a knowledge institute. But also in many other cases, references to Africa are inappropriately made. Newspapers for instance continue to report about Africa, even where specific countries are involved. The Volkskrant, a Dutch newspaper, for example reported that a mammoth was found in Africa. This may come across as a small and unimportant illustration, but what prevented the newspaper from putting Namibia in the title? It was Namibia after all where the remains were found.

Due to the Ebola outbreak, there is currently increased attention to the continent. Attention that is highly needed (as are donations!), but that is also exemplifying the omnipresent stereotyping. The various BandAid initiatives are the best examples of this. The songs convey images that might prove useful to raise money, but also maintain stereotypical views on the continent. The Dutch BandAid`s Ebola song, for example, tell us that `It`s not a white Christmas that Africa is missing this year, their gift is who survives`, whereas Bob Geldof`s BandAid uses lyrics as ` No peace and joy this Christmas in West Africa. The only hope they’ll have is being alive`. As many critics have argued, these texts exemplify an ignorance of Africa and reinforce a white savior narrative. Furthermore, several artists from across Africa have also produced a song and in Sierra Leone I have friends who produce educational videos and songs to combat Ebola. These more local initiatives are generally ignored.

Moreover, although Ebola clearly exemplifies these narratives, they are always present: Africa as a country, a place of poverty and sadness, a place where there is no space for happiness and thus no Christmas joy, and a place that needs the West.

Let it be clear, I do support initiaves that aim at raising funds to combat the problems. This is highly needed, as health infrastructure is weak and governments and people face challenges in addressing the issues, for too many and complex reasons to discuss here. The point is not that I doubt the necessasity of raising money or even the goodwill behind the songs. The point is that songs like this, newspaper articles about mammoths or ridiculous visa or travel regulations, portray and mantain ignorant ideas and fears of Africa and Africans, often resulting in feelings of superiority and sometimes even racism. Thus, yes support the international fight against poverty, but let those who engage in opinion making be aware of the consequences of the stereotyped messages that they often convey. Life entails more than sadness, also in the poorest African countries.

A noble poor?

Indeed, life entails more than sadness, also in the poorest African countries. Africa is not simply the arena of sadness, war, hunger, corrupt governments and development organizations. Yet, stereotyping does not only occur in the domain of misery. Some stereotypes take it to another level and apply a good deal of romanticism, a discourse that situates the African as a `noble poor`.

The noble poor can be seen as a discourse that often portrays poor people as victims of uncontrollable, regularly external, forces that hinder their development. Of course this is part of the story: many people in the world fight for survival on a daily basis and are victims of powerful systems of inequality. Yet, problematic is the overemphasizing of this part of the story and the tendency to romanticize poor people and their struggle, thereby ignoring internal issues that might be counterproductive in their daily struggle and could even reinforce the unjust system people themselves are suffering from.

Such romantic views are found in expressions that celebrate poor people`s strong will to optimally use the little possibilities they have, despite the unfair obstacles they face. It celebrates people as survivors who are, despite their poverty, very happy in a life close to nature without the burdens of modernity. The noble poor is created: a person whose concern is fighting for the life and wellbeing of their family and community, who is appreciative, thankful, honest and hard-working. This poor person might be poor, but morally superior.

Often, these ideas are associated with different forms of community romanticism. The idea that life in small communities is peaceful, where people solve internal issues quickly, where the little they have is shared among the many that need. Commonly, these views celebrate the `local` and are geared towards conserving it, while addressing development challenges. An example is the focus on African people as natural (small-scale) farmers often based on figures regarding the percentage of people that are engaged in farming or an idea of farming as a traditional lifestyle. However, just because people are engaged in farming does not mean that they like to farm: in many cases, people have always been farming because there was simply no alternative. Other examples celebrate local knowledge as superior to external knowledge. Of course, local knowledge is highly important, yet societies continuously change and always find their worldviews and knowledge challenged by a world outside the local community. This is a very normal process. Moreover, during the Ebola outbreak, for example, it was obvious that certain types of knowledge and practices, such as funeral rituals, were not suitable to combat the outbreak. A process of conversation started and now proves to be constructive.

Just as the misery stereotype, a conservational and romanticizing approach on Africa and African people`s problems, needs, and desires, is also unsatisfactory. As long as we continue to keep up romantic views on the poor, ignoring social structures underlying poverty issues, we just engage in a game of seeking external explanations. Whilst these explanations might be truly valid, they can never be exclusive.

An informed normal-people perspective

Despite a series of outcries, such as the famous essay by Binyavanga Wainaina `How to write about Africa` and the website www.africasacountry.com, popular discourse on Africa finds itself at two unsatisfactory and stereotyping ends. The one is a view depicting Africa as a place inhabited by helpless people that long for salvation; the other one a view that romanticizes communities and people and establishes an idea of a noble poor. The ongoing confirmation of a paternal and ignorant perspective, be it the helpless savage or the noble poor, is fundamentally abject and will not lead to satisfactory contributions of any kind in the long run.

Ebola highlights that we still have not moved away from stereotypes. It is time to put into practice the knowledge that Africa is a continent consisting of distinct countries. All of these are inhabited by normal people: people that can be nice, honest, deceptive, thankful, uninteresting, interesting, grumpy, dishonest, unmotivated, knowledgeable, ignorant, encouraging and active. People. Just like anywhere else in the world. And yes, the continent has its specific characteristics and problems, as do the continent`s different countries. But these need to be addressed in a respectful, realistic and informed way that does not draw upon simple stereotypes, but seeks to eliminate ignorant views on Africa.

Robert J. Pijpers is a PhD candidate, Department of Social Anthropology, University of Oslo

A shorter version of this article was first published at opendemocracy.net

0 Comments

1 Pingback