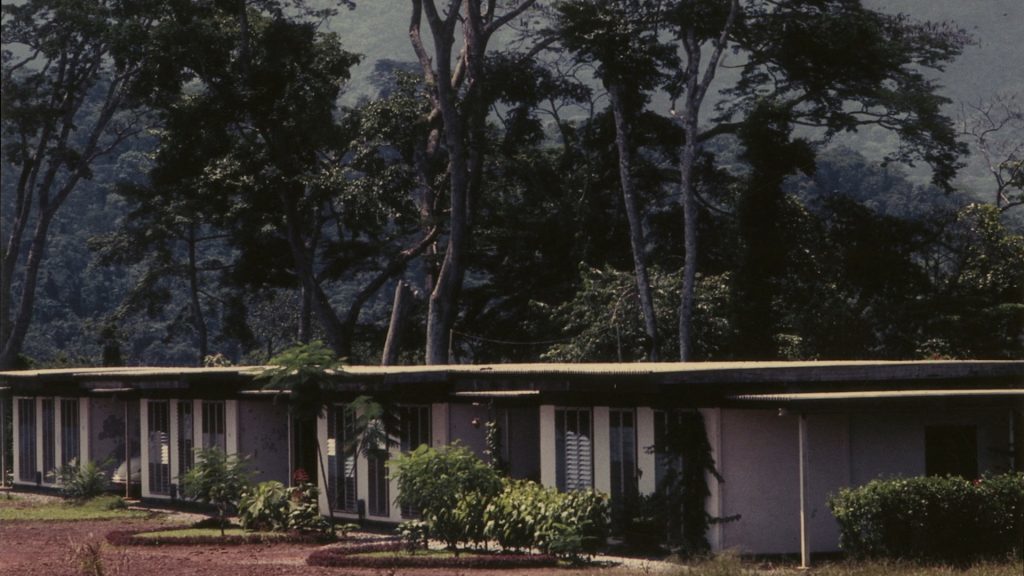

Still from the film Uppland

Around the 23-minute mark in the short film, Uppland, an unidentified voice speaks over a series of historical images of Yekepa, Liberia. Male and American, the speaker is presumably a former resident of the town. Yekepa was a LAMCO company town in Liberia’s Nimba Mountains, home to hundreds of the Swedish mining conglomerate’s employees. “Life was pretty nice there,” the voice says. “But you weren’t really living in a real world.”

Edward Lawrenson and Killian Doherty’s short film is conceived as an archeological project, an excavation of the physical and psychic ruins of industrial mining in West Africa. Lawrenson, a Scottish filmmaker and writer, and Doherty, a Northern Irish architect, set out for Liberia after Doherty comes across photographs of Yekepa from the 1960s and 70s. Such images are not hard to find. Iron ore mining was a central pillar of Liberia’s post-World War 2 economy. Foreign mining giants like LAMCO, backed by the Liberian governments of William Tubman and then William Tolbert, rapaciously harvested the country’s reserves until the global price crashes of the 1980s. Today the detritus of company towns and massive iron ore pits litter northern and western Liberia. These ruins occupy a prominent place in the lives and memories of Liberians and non-Liberians who inhabited the mines and their supporting towns. The “pretty nice life” that iron ore mining made possible is a complicated and important thread in the story of Liberia. So, too, are the consequences of a political economy that so thoroughly shaped the “real world” of most of Liberia’s inhabitants.

Still from the film Uppland

Lawrenson narrates the film and describes the origins of both the town and the project, though fortunately he dispenses with the usual filmmakers’ journey and arrival tropes. The visuals are primarily scenes of ruins: abandoned industrial equipment and infrastructure; housing; and the terraced hillsides and massive pits carved into the mountains. The film’s 30-minutes are divided into four variously timed chapters. The first, Yekepa, is ostensibly anchored by the contemporary town. A small population still lives there, including at the gated campus of ABC University, a Bible college. Old Yekepa, the brief second chapter, is framed by a visit to the abandoned village of Yeke’pa. The Bible college’s carpenter happens to be a community leader among the population displaced by the mining operation, and he leads the filmmakers back to the village’s original site. New Yekepa, the third chapter, travels to the site to which the displaced were relocated. There the residents describe the inadequacies of their compensation and tell their own version of how geologist Sandy Clarke discovered the iron ore deposit and captured the mountain’s guardian spirit. The final chapter, Stockholm, briefly brings the film to the apartment of a retired couple who describe the suburban Stockholm aesthetic of Yekepa and the failure of the company to leave much of anything behind.

Each chapter weaves together historical still and moving images, on-camera interviews, and beautifully shot observational footage. Given that neither Lawrenson nor Doherty are ever named or made visible in the film (Doherty is simply referred to as “the Architect”), Uppland is surprisingly personal and reflexive. Lawrenson speaks frequently in the first person and includes both narratives and visuals that make the filmmaking process an engaging subplot. For example, the filmmakers cleverly include a few seconds of footage of Thomas, a young man assigned to keep an eye on Lawrenson, trying in vain to direct the action of people walking into and out of the camera frame. Uppland avoids most of the pitfalls of the narrated, exploitation documentary genre, its disembodied voice-over never becoming too authoritative, outraged, or self-indulgent—a rare achievement in this ever-expanding field.

Still from the film Uppland

The sum total of the film is nevertheless familiar. It is a galling portrait of the harvesting of African resources and the damage done to both land and people. The mountain that once housed the deposit is now a giant stagnant lake. New Yekepa appears as a soulless, impoverished, and somewhat embittered place. The Swedish retirees, meanwhile, are surrounded by a national museum’s worth of artifacts in their bright, comfortable looking apartment. And everywhere there are rotting husks of metal and concrete, useless now that the mine has closed.

Both visually and narratively, Uppland is too clever and interesting a film to stop at that. “Life was pretty nice there, but you weren’t really living in a real world” is a line that could arguably have been spoken by everyone in the film and everyone behind it. Certainly, this is true of the white foreigners who worked for LAMCO, who appear in their greatest numbers in swim trunks, splashing around in the company’s swimming pool. The Swedish retirees speak of their intentions to leave a sustainable economy at Yekepa, but “it’s a pity” is the best they can offer as commentary on the fact that they failed to do so. The American professor at the Bible college certainly seems to be having a good time, but his alienation from the “real world” around him is absolute. His earnest Old Testament history lesson about the disappearance of manna is deliciously apropos of the surrounding context but obviously lost on the man himself.

Still from the film Uppland

That the past was better but never real even for the Liberian residents of Yekepa is painfully clear in a conversation with two men named John, both former local employees of LAMCO. They fondly recall the town’s hospital, schools, and ice cream shops, all of which they claim made the residents of the town feel like they were “living in America” right there in the rainforests of northern Liberia. But they are unreliable narrators. One of the Johns describes the perfect racial harmony and integration of Yekepa, but there are no black bodies in the swimming pool images; a line of school children shows whites in the front and blacks in the back; and footage of a white Swede tending his vegetable garden is contrasted to a young Liberian houseboy stripped to the waist mowing the lawn.

The ruins of Yekepa make everyone look to the past and complicate their relationship to the real present. The residents of New Yekepa implausibly claim that their lives today would be better if only they hadn’t lost the written resettlement contract Clarke gave them when he forced them to move. And as the film abruptly ends, audio clips of President Tubman’s 1962 speech to LAMCO employees extol the virtues of mining, celebrating the company’s commitment to exploiting a wilderness inhabited only by spirits and bringing both wealth and civilization to Liberia’s upplands. The visuals, of course, are of a scarred landscape and still, rusting machinery.

In the film’s penultimate moment Lawrenson describes being approached by security guards as he filmed those ruins. It is cutting testament to the slippery unreality of memory and hope when they ask if he is here to restart the mine. Lawrenson smartly spins the encounter into a comment about his own position; the filmmaker must pack up and depart for Europe before he can engage them in meaningful dialogue, taking away the richness of his film and leaving them with their disappointment and their ruins. But the moment is more poignant than that. Rising world iron ore prices have led a number of multinational companies to revisit Liberia’s abandoned mine sites, and iron ore now accounts for about 30% of Liberia’s foreign export earnings. Small enclaves of foreign workers are building new company towns that are largely off-limits to local residents, who continue to inhabit the ruins of the old company towns. New mining equipment and infrastructure is being imported to do the work, much of it less dependent on human labor and therefore even less dependent on the “real world” of the people who live around it.

What kind of ruins this new mining economy will leave, and how they will be remembered, will no doubt be the subject of a film to come.

Danny Hoffman is Associate Professor of Anthropology at University of Washington.

This text originally appeared on the blog Africa is a country