During the second part of this spring sociologist Ugo Corte and I will teach a new master course in the Ethnography of the senses here at Uppsala University. I have over the last few years tried to encourage students in both using other technologies during fieldwork and also opening up for other outputs than the traditional essay. One student who took the challenge was David, at the time a BA student at the department, who went to Malta for a workshop in Graphic Anthropology. Here is his take on graphic anthropology.

Familiar with Graphic Anthropology? Didn’t think so… Neither was I before I was forwarded an e-mail for an upcoming workshop on Malta(!) last March. It turned out that some sort of renaissance in the ways of using fieldnotes accompanied by drawings was taking place. At least as a part of doing participatory observations in fieldwork and as one method of Visual Anthropology. Not knowing where it would eventually take me I started filling out the workshop’s application online…

Situated on Gozo in the Mediterranean, Malta’s second island, the location and timing for the workshop couldn’t have suited my BA-thesis-angst better! Through its proximity to rich historical sights, rural beauty and the widespread local knowledge of English (formerly under British rule) I ended up spending a fortunate couple of sunny weeks abroad. A dichotomy of academia/creativity (ironically speaking) was the tension my studies didn’t know I’d missed. Let me introduce you a little of how the workshop in graphic anthropology has changed my understanding of academic research in anthropology as both a theoretical rite-de-passage as well as a self-reflexive process.

Hosted by program director of the organization Expeditions, Sam Janssen and a team of his helpful staff, the Graphic Anthropology Field School (GrAFs) was held for the first time and accommodated during Easter near Xlendi.

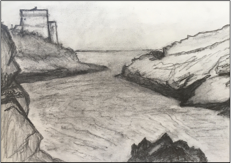

Xlendi Bay. A picturesque village often seen on touristy postcards from Gozo. Turquoise water, a small and cliffy beach promenade and the approximately 400 years old Xlendi Watchtower next to the ocean’s inlet, made this Gozitan site a drawing-friendly view.

What about the method of doing graphic anthropology then?

The conduct of using graphic methods as a way of doing research in fact has its origins back in the early days of Bronislaw Malinowski, and the time when visual complements were noted in his travel diaries while doing fieldwork. Visual representations together with text were also used as margin notes and captions in Margaret Mead’s and Gregory Bateson’s photographic analysis in Balinese Character (1942). Prior to its anthropological implementation, the use of illustrations were embedded in other scientific excursions. Hired artists accompanying the likes of Swedish botanist Carl von Linné on their expeditions apparently influenced an early version of performing anthropological fieldwork.

Industrial and technological development together with scientific discoveries in the1800s and early 1900s seemed to favour photography as the most ‘objective’ way of documenting an object. Drawings, with or without the company of text, became considered simplified and not as accurate in the academic sense. Graphic anthropology was overshadowed by new technical advantages and scientific ideals such as being neutral and may be a reason for the submissive extent of the graphic method compared to photography.

Graphic anthropology combines several creative genres. Whether in the form of doodles or simple illustrative journaling-sketches, as well as through ethnographic drawings (in fact a great self-reflexive conversation starter while on the field) or even expressed as comics. At times ‘native drawings’ have been used by some anthropologists to demonstrate how ‘the others’ were thinking and understanding the world, but oftentimes reproduced post-colonial and Western hegemonies in research rather than contributed to a deeper ‘inside’ perspective. Current trends in graphic anthropology (for instance heeded by Tim Ingold) view the fieldwork rather as a cooperative experience, where the reflexive part and the anthropologist’s impact on site is crucial for careful decision-making before, during and after fieldwork.

Self-reflexive drawing from doing participatory observations in downtown Victoria (Rabat). Causing both curiosity and non-provoked interaction among the interlocutors on a small but ‘friendly’ island.

Using drawing as a means of starting conversations while doing fieldwork is, according to my experience, the graphic method’s fundamental strength. Depending on one’s positioning as an observer, individual skills and/or the portrayed object(s) interaction, the method usually ignites curiosity. It may also turn out relevant as a nice gift of reciprocity to an interlocutor after a graphic session or an open-ended/semi-structured interview.

The GrAFs also pointed to an increased awareness of differing visual understanding of photography and visual portraying. Previously understood as showing things fixed ‘as they are’, photography has in later research been understood as part of a society’s larger mediascape (see Appadurai’s Modernity at Large) and is commonly not viewed as more objective than a drawing. The selective process of doing graphic notetaking (i.e. which motifs, materials to use and objects to emphasize) is probably more ‘alive’ for the reader on the process than the results of taking a photograph (see Taussig’s I swear I saw this). This implies a culturally specific understanding of photography as well as in graphic anthropology. The failed and outdated objectivity claims of photography have opened up for a revitalization of graphic anthropology giving it renewed credibility and interest.

In an extensively relativistic, or ‘post-truth’, society this may entail a complementary or even counter-narrative function of graphic methods (see Taussig). Where photoshopped photography and digitally edited videos fail at showing the world as it truly is, perhaps a drawing or graphic comics appeal less pretentious? The subjectivity in and processual approach of graphic anthropology may despite new technological advancements in other media be one of the causes behind its return. Looking at recent decades of popular culture, but also common in traditional news media, the rise of genres such as graphic novels, graphic journalism (i.e. Joe Sacco) and satirical drawings, we may find confirmation to its relevance. Finally, a drawing’s ability to mediate an implicit feeling compared to in text/photo has been studied by anthropologist Michael Taussig, and is, borrowing from Roland Barthes, described as ‘the third meaning’. As far as I’ve understood, this theory implies graphic drawings/notetaking as an alternative way of communicating reality, transcending a message that meets the eye.

Authentic charcoal-drawing from GrAFs and the field trip to a local blacksmith, ‘Master Wenzu’. Many companies are family-driven on Gozo and the profession has lived on through the generations, in Wenzu’s case for more than 100 years.

David Johansson

Further reading

Afonso, Ana Isabel. 2011. “New graphics for old stories. Representations of local memories through drawings” in Working images. Visual research and representation in ethnography. London and New York: Routledge.

Appadurai, Arjun. 1996. Modernity at Large: Cultural Dimensions of Globalization. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. 1st ed.

Bateson, Gregory and Margaret Mead. 1942. Balinese Character: A Photographic Analysis. The New York Academy of Sciences. Volume II.

Hoffmann-Dilloway, Erika. November 4, 2016. Chatting While Waterskiing. Part 1-3. http://www.upteachingculture.com/tag/erika-hoffmann-dilloway/ [Accessed 2016-12-01 14:57]

Ingold, Tim. 2013. Making. Anthropology, Archeology, Art and Architecture. London and New York: Routledge.

Malinowski, Bronislaw. 1989 [1967]. A Diary in the Strict Sense of the Term. London: The Athlone Press.

Taussig, Michael. 2011. I swear I saw this. Drawing in fieldwork notebooks, namely my own. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Tondeur, Kim. October 17, 2016. Graphic Anthropology Field School. http://somatosphere.net/2016/10/graphic-anthropology-field-school.html [Accessed 2016-12-01 14:46]

Robben, C.M.G. and Jeffrey Sluka. 2012. “Part IX Reflexive Ethnography” in Ethnographic Fieldwork. An Anthropological Reader. pp. 513-517

Leave a Reply