Preamble, Sumba, March 2025

My desk is facing the beach and ocean. I am currently on the small Indonesian island of Sumba, and my Californian neighbour is hitting the waves with his board. Back in 2017, I worked on a text about surfing, trying to compare the surfboard with the gun given to poor young men in West African civil wars. I even interviewed young surfers in the sleepy town of Robertsport, Liberia. It was a bit of a crazy comparison, but they often end up being the coolest, or so I thought then. I never finished the text, and as with the many other half-written ones on my hard drive, I probably never will. But re-reading it, I thought I should share it here the way it was and also take the opportunity to show some of the pictures I took back at Robertsport. My friend sociologist Ugo, who first inspired me to think about surfing, finished his research on the matter and published a great book with the University of Chicago Press (see readings by the end of this text). Although I took a surf lesson in Sierra Leone a few years ago, I still need to learn to surf!

This paper is based on two similar observations in the same country, but twenty years and worlds apart. It is a paper about the ludic and the vexing, about the fancy and fierce, about flow and the sublime.

During the spring (2017), I taught a master’s course with Ugo Corte, an Italian sociologist. Together with a bunch of students, we explored literature about the sensorial in anthropology and sociology. Ugo is, amongst others, doing research on big wave surfing in Hawaii, and to find a common denominator, I, when I was in Liberia last fall, decided to spend a few days amongst Liberian surfers in the tiny fishing town Robertsport. What follows is an altered version of the presentation I gave the master’s students.

In the full version of the paper, I will start with two questions: What is the gun to marginal youth in wartime Liberia? And what is the surfboard to marginal youth in post-war Liberia? I then want to pair these findings with the concepts of sublimity and flow, which are activity-prone concepts. While Csikszentmihalyi’s Flow is pretty straightforward, I intend to dwell a bit more on the Kantian sublime. I do so by using Brian Larkin’s Signal and Noise. I do acknowledge his rather unique way of using the concept. Thus, I will contrast/compare this with Richard Klein’s pomo classic Cigarettes are Sublime and how Simmel and Lyotard use the idea. I re-read Klein this summer, but my holiday was too short and sweet to allow me to develop this sufficiently. The simple aim I have here today is to convince you that there is potential research merit, i.e. it is not just a theoretical exercise, combining gun and surfboard in a sublime flow of war and post-war Liberia.

So Kant’s basic definition is that objects become sublime only because we judge them in reference to other objects (Larkin p. 35). Kant divided the sublime into two parts: the mathematically sublime, based in a sense of magnitude, and the dynamically sublime, the feeling of overwhelming physical powerlessness individuals feel in the face of something overpowering and terrible, which is fueling ambivalence “a simultaneous appreciation of beauty, awe, and terror”(Larkin p. 36).

Larkin focuses on the sublimity of technology and the awe that colonial technology spurred among Nigerians. The obvious technologies of the time were the train and the mobile cinema. David Nye, quoted by Larkin, proposes that “the technological sublime does not endorse human limitations; rather, it manifests a split between those who understand and control machines and those who do not” (Larkin, p. 39).

In Larkin’s work, he looks at colonial technologies from the point of view of the marginal colonial subject, but I propose a similar framework today for Liberia, a country that was de facto never colonized. Modern technologies such as the gun and the surfboard are related to awe. Still, I argue that in addition to technological awe, they may be considered sublime in the Kantian sense, as gun and board are also technologies for mastering, at least playing, flirting with, or surviving (at times sensing flow) of the otherwise overpowering and terrible.

In the water, youngsters eagerly wait to catch the right wave. Once they land with surfboards on the beach, they return to the cape and paddle out again. A theatre is going on for the entire day, and boys and young men battle over who may use the few available boards. Liberian youth are indeed, just as we are, also homo ludens, but this is actually a frenzy I have rarely seen in the country. When I asked them about surfing, they told me about experiencing the flow of life.

Almost twenty years before this experience, I recorded similar sentiments of flow amongst young Liberian rebel soldiers when they described attacking enemies on the battlefield.

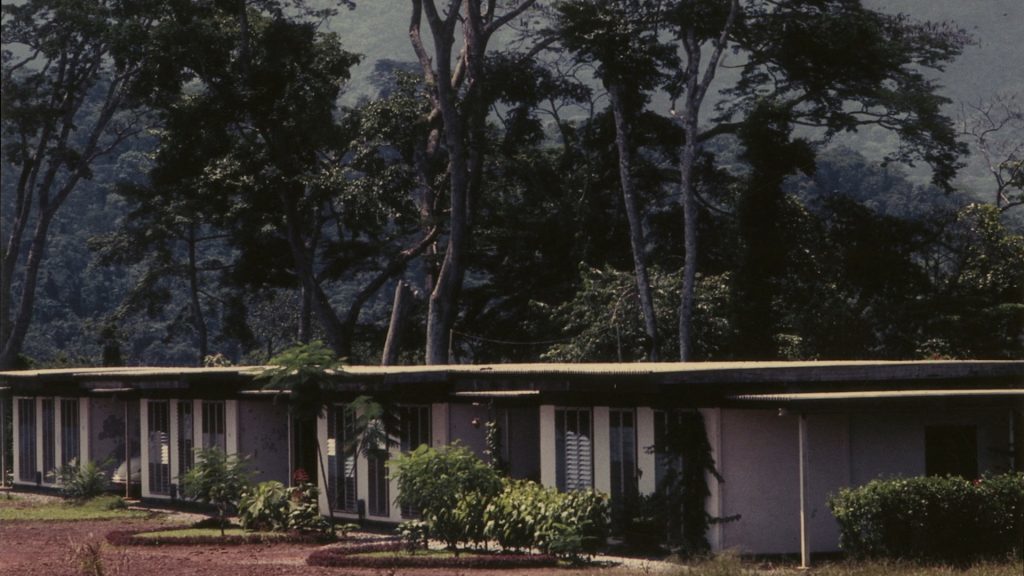

When I started researching young combatants, it was 1997 in Monrovia. The rebel leader Charles Taylor had just won democratic elections to the great dismay of the West and the global humanitarians. My first field spot was called the Palace – a palace of misery. An abandoned concrete structure, an old factory quite centrally situated in downtown Monrovia. In the Palace, former combatants squatted and survived in the margins of the marginal in all senses: politically, economically and socially. By the majority, they were seen as scum of society, the utmost lumpen of lumpens. That international aid workers who resided nearby bizarrely enough believed them to be cannibals only further reiterated their marginality.

My second field spot was in the Liberian interior where I worked with a group of former combatants leading slightly better lives. They were sons and daughters of the soil. In the aftermath of the first Liberian war, they fought hard to get re-integrated: they earned money that they used for school fees, they visited the villages where they came from and brought gifts to restore social relationships, and in all ways possible, tried to repair what was broken and regain what was lost. To them, the whole war had been about locating opportunities and fighting their way out of the rural margins and often precarious social relations.

My third and longest fieldwork lasted two years as I hung out on a street corner in Freetown, Sierra Leone. Here, I more than ever took part in everyday life, and I believe that I, in a very detailed way, got to understand their life realms, both in hindsight with regard to their experiences as fighters during the war in the country and also their survival in post-war settings.

But my work was hardly embodied. I did not experience the war as a rebel soldier. I did not kill, I did not maim people, I did not loot or burn down people’s property. I did not dodge bullets, and I did not starve in the jungle. My commander didn’t mock-execute me because I did not share my loot. I did not, for the first time, experience the power of deciding who should live or die, the rush of rape etc.

And on the post-war street corner? I did not sleep outdoors in the pouring rain. Fight for food on a daily basis. I did not smoke crack cocaine. I did not experience jail first-hand. My friend was not slashed to death with a knife in a meaningless turf war. And I did not experience the demeaning moments of letting another man sleep with my girlfriend because I could not afford to feed her.

I could talk at length about how a marginal rebel soldier feels during the war to make sense of the flow they sometimes experience on the battlefield, but it has been done elsewhere. Yet still, think for a second how it would be to live in a very poor country, run by a very small elite, controlling most political and economic resources. You grow up with poor parents in a gerontocratic village. Most certainly, your parents can’t afford to educate you; the land you will farm is somebody else’s – it is not yours. When war comes, either the elders in your village decide that you must join the rebel movement to protect land and people, or you are more conscious and run away because you see the war as a means to liberate yourself.

It was a kind of patience-my-ass-move. I took a picture of a boy in a t-shirt with that print at a checkpoint manned by the rebel movement NPFL in Saniquelle in 1996. At the time, I did not know it, but this fuck-all mentality, a mentality implying the need to take whatever chance there is to get somewhere in this world, came out strong in many of the life stories told by former combatants both in Liberia and Sierra Leone.

Being from the margins of the very margin meant for quite many that the gun, to some extent, was the first piece of modernity they ever laid hands on. Others have accounted for the fantasy energy young combatants felt when given a gun – the gun itself was a sublime object. The power of the gun only accentuated this. What you could get by holding a gun was sensational: all the food you could eat, a car, make the elders kneel in front of you, a house, you could have a bed, where you could even host your first girlfriend or command a woman to have sex with you. It was sensational. It was a rush. It was power. It was living with speed. It was flow.

Back then, I named my PhD thesis “Sweet Battlefields” after an ex-fighter in one of my interviews told me that “there is nothing as sweet as being on the battlefield when fighting is going fine”. What he alluded to then, something I also heard from many others, was a double feeling of flow. Flow is, according to Csikszentmihalyi, “[t]he holistic sensation that people feel when they act with total involvement” (p. 36). And to the fighter flow was experienced and embodied, partly directly, momentarily on the battlefield when fighting was going fine, but more often, it was part of the edgework of being a rebel which they lived and embodied (and certainly missed in the aftermath as they were momentarily remarginalised). The gun is utility, sublimely beautiful, although involving both fear and blockage (Klein p. 63).

Ugo points out that a big wave surfboard is sometimes called a gun, or an elephant gun, to be more precise. Although waves are radically smaller on the Liberian coastline than off Hawaii, and you certainly don’t need a gun, I will shift time and space, traverse back to the present day and to ocean, swell and surf.

I propose a link between surfboards and guns in a slightly different way than the idea of guns amongst big-wave surfers offshore in Hawaii. I do so by suggesting that to youth in the Liberian margins, both objects are “totems of technology” breeding on “fantasy energy” (Larkin p. 126). To the marginal comrades in the sleepy town of Robertsport, surfing creates a similar flow as war, and the surfboard is a modern object of technology (ibid. 20-21) akin to the gun.

There is generally a lot of foot-dragging and slow movements among marginal youth in West Africa. It is as if their whole bodies protest against the dominant society (in the sense proposed by James Scott). Indeed, if paid opportunities turn up, young bodies may pick up speed. But it is rare, so when I watch surfers quickly getting out of the water and running back to get in, I react: this drama is a Liberian rarity. This is flow. I ask them how they feel when they surf; indeed, they contrast surfing to the hardships of everyday life. When they wait for the right wave and ride it, they are the masters, and on the beach, the elite from the capital sits in the shade, watching in awe. Tables are turned for as long as they are in the water.

“People who don’t know it say we make magic”, one of the young surfers states.

In Mark Stranger’s book Surfing Life, he discusses the surfer as an adventurer in Simmel’s tradition. They are “aesthetically oriented leisure-time risk-takers”, pseudo-adventurers only mimicking real “heroic life” (p. 160). One may argue that this is also at stake in Robertsport. Leisure has replaced warfare, and controlling waves have replaced social navigation of war; “the surfer appreciates nature in a stormy sea” and “finds purpose in this sublime chaos” (p. 163).

“The appreciation of the sublime is facilitated by the experience of flow and the meanings attributed to it in surfing culture”, states Stranger and continues to say that “the ecstatic feelings of universal oneness that an appreciation of the sublime can induce are intensely experienced in the transcendence of self-immanent in flow” (ibid.). But maybe this is only post-modern mimicking. After all, as Simmel states, the real adventurers’ thrill of risk-taking involves: “complete self-abandonment to the powers and accidents of the world, which can delight us, but in the same breath destroy us” (p. 193). This sounds more like the sublime flow of the Kalashnikov-toting youth of the civil war than of the beach boy surf dude of the post-war. The gun in a sweet battle, but not the surfboard in a good swell, is a “negative pleasure” in Kant’s eyes.

Readings

Csikszentmihalyi. 2000 [1975]. Flow

Kant. 1952. The critique of judgement

Corte. 2022. Dangerous fun

Klein. 1994. Cigarettes are Sublime

Larkin. 2008. Signal and noise

Lyotard. 1994. Lesson on the analytic of the sublime

Simmel. 1971. The adventurer

Scott. 1985. Weapons of the weak

Stranger. 2011. Surfing life

Utas, 2003. Sweet battlefields